DEEL 4 | 4 DECEMBER 2021 – 15 JANUARY 2022

The content of Article III explains what is meant by the vertical separation of powers between the Member States and the federal body. Because the Member States have common interests that they cannot defend on their own, they entrust some of their powers to a federal body. They do not transfer their powers but make them dormant, as it were. Their sovereignty remains unaffected. The federal body serves the common interests of the states with powers of the states. If the federal body mishandles the powers of the states, that 'dormancy' of the powers is reversed because - in accordance with Article I of the Constitution - the federation is the property of the Citizens and of the States.

Well, Article III is mainly about that exhaustive list of powers of the federal body for the promotion of common interests of the member states. Note well: the Preamble is about values, Article III is about how the federation will try to guarantee those values.

Section 1 is important from the point of view of revenue of the federation. The House of Citizens may make tax laws while the Senate may make proposals to amend them: checks and balances.

Both Houses may draft federal laws. This differs considerably from what is customary in most countries. There, governments draft laws and parliaments act as the bodies to enact or amend them. This power of the legislature to draft laws itself forces the President to accept them for implementation or not. If not, a process of arguments and counter-arguments takes place in which the number of votes within the legislature ultimately determines who wins.

Section 2 of Article III is the exhaustive list of powers of the European Congress. What the President, as head of the executive, may do with it is stated in Article V on the powers of the President. I will deal with that later.

Again: the Preamble contains the values that the federation wants to preserve, Section 2 of Article III is about the list of limitative powers of the legislature to protect those values. So that list is not about policy, for example about reducing CO2 to protect the climate. That the legislature can make policy on that point is stated in Section 2 under g: "to regulate and enforce the rules to further and protect the climate and the quality of the water, soil and air;". But it is up to the members of the European Congress to decide what the content of that policy will be. The constitution is not left-wing, not right-wing, not progressive, not conservative. It provides the basis for setting a political course with policy measures. But what those policies will be is determined by the members of the House of Citizens and the Senate.

Members of the 55+ group who wish to table amendments for Section 2 are asked to use this level of abstraction. An amendment along the lines of: "The USE is reducing CO2 emissions by 50% by the year XX" is not useful. That is policy and has no place in a constitution.

Once again. The constitution has no political colour. It is the 'common house' in which we all have to live, looking for happiness, prosperity, and freedom, as much as possible. If we build a constitution based on specific policies, we will easily attract people, organisations and parties that are in favour of those specific policies, but we will lose the support of all other persons, organizations, parties. A federal constitution must not be a Socialist constitution, it must not be a Christian Democrat constitution, it cannot be left, or right, or whatever. It is a constitution for all European citizens and for all European countries and regions. And that must be expressed in words of constitutional law. Not in words of politics and policies.

In Section 3, the first Clause states that immigration policy of individual states will be phased out and become a federal matter after XX years. The implicit reservation that member states may first pursue their own immigration policies for some time dates back to the time when a treaty-based common EU policy not yet existed. Therefore, this is a good Clause to amend in the sense that immigration policy is a matter for federal authority from the outset.

Sections 4 and 5 contain provisions limiting powers. In Section 5, Clauses 4 to 9 contain strict provisions to prevent political corruption. Influencing elections and policy with money must be out of the question.

Artikel III... Bevoegdheden van de wetgevende macht

Sectie 1 - Wijze van totstandkoming van wetten

- Het Huis van de Burgers heeft de bevoegdheid om belastingwetten voor de Verenigde Staten van Europa in te stellen. De Senaat heeft de bevoegdheid - zoals ook het geval is met andere wetgevingsinitiatieven van het Huis van de Burgers - amendementen voor te stellen om de federale belastingwetten aan te passen.

- Beide Kamers hebben de bevoegdheid wetten in te dienen. Elk wetsontwerp van een Huis wordt voorgelegd aan de President van de Verenigde Staten van Europa. Indien deze het ontwerp goedkeurt, ondertekent hij het en zendt het naar de andere Kamer. Indien de President het ontwerp niet goedkeurt, zendt hij het, met zijn bezwaren, terug naar het Huis dat het ontwerp heeft ingediend. Dat Huis neemt de bezwaren van de Voorzitter op en neemt het ontwerp in heroverweging. Indien na deze heroverweging tweederde van die Kamer instemt met de aanneming van het wetsontwerp, wordt het, met de presidentiële bezwaren, naar de andere Kamer gezonden. Indien die Kamer het wetsontwerp met een tweederde meerderheid goedkeurt, wordt het wet. Indien een wetsontwerp niet binnen tien werkdagen nadat het bij de president is ingediend, door deze is teruggezonden, wordt het wet alsof hij het had ondertekend, tenzij het Congres door de onderbreking van zijn werkzaamheden verhindert dat het binnen tien dagen wordt teruggezonden. In dat geval wordt het geen wet.

- Bevelen, resoluties of stemmingen, andere dan wetsontwerpen, waarvoor de instemming van beide Kamers is vereist - met uitzondering van besluiten tot verdaging - worden aan de Voorzitter voorgelegd en behoeven diens goedkeuring voordat zij rechtsgevolgen hebben. Indien de Voorzitter dit afkeurt, heeft deze aangelegenheid toch rechtsgevolgen indien twee derde van beide Kamers ermee instemt.

Afdeling 2 - Materiële bevoegdheden van de Kamers van het Europees Congres

Het Europese Congres heeft de macht:

- belastingen, imposten en accijnzen te heffen en te innen ter voldoening van de schulden van de Verenigde Staten van Europa en ter voorziening in de uitgaven die nodig zijn om de garantie te vervullen als omschreven in de preambule, waarbij alle belastingen, imposten en accijnzen in de gehele Verenigde Staten van Europa uniform zijn;

- om geld te lenen op het krediet van de Verenigde Staten van Europa;

- om de handel tussen de staten van de Verenigde Staten van Europa en met vreemde naties te regelen;

- in de gehele Verenigde Staten van Europa uniforme migratie- en integratievoorschriften vast te stellen, welke voorschriften mede door de staten zullen worden gehandhaafd;

- om uniforme regels voor faillissement in heel de Verenigde Staten van Europa te regelen;

- de federale munteenheid te munten, de waarde ervan te regelen en de standaard van maten en gewichten vast te stellen; te voorzien in de bestraffing van vervalsing van de waardepapieren en de munteenheid van de Verenigde Staten van Europa;

- de regels te reguleren en te handhaven om het klimaat en de kwaliteit van het water, de bodem en de lucht te bevorderen en te beschermen;

- om de productie en distributie van energie te regelen;

- het stellen van regels ter voorkoming, bevordering en bescherming van de volksgezondheid, met inbegrip van beroepsziekten en arbeidsongevallen;

- elke wijze van verkeer en vervoer tussen de Staten van de Federatie te regelen, met inbegrip van de transnationale infrastructuur, postfaciliteiten, telecommunicatie alsmede het elektronische verkeer tussen overheidsdiensten onderling en tussen overheidsdiensten en burgers, met inbegrip van alle nodige regels ter bestrijding van fraude, vervalsing, diefstal, beschadiging en vernietiging van postale en elektronische informatie en de informatiedragers daarvan;

- de vooruitgang van de wetenschappelijke kennis, de economische innovaties, de kunsten en de sport te bevorderen door aan auteurs, uitvinders en ontwerpers de exclusieve rechten op hun creaties te waarborgen;

- om federale rechtbanken op te richten, ondergeschikt aan het Hooggerechtshof;

- piraterij, misdrijven tegen het internationaal recht en de mensenrechten te bestrijden en te bestraffen;

- de oorlog te verklaren en regels vast te stellen voor de gevangenneming te land, te water en in de lucht; een Europese defensie (leger, zeemacht, luchtmacht) op te richten en te ondersteunen; te voorzien in een militie om de wetten van de Federatie uit te voeren, opstanden te onderdrukken en indringers af te weren;

- alle wetten te maken die nodig en passend zijn voor de uitvoering van de voorgaande bevoegdheden en van alle andere bevoegdheden die deze Grondwet toekent aan de Regering van de Verenigde Staten van Europa of aan enig ministerie of enige overheidsfunctionaris daarvan.

Afdeling 3 - Gewaarborgde rechten van personen

- De immigratie van personen, door staten die als toelaatbaar worden beschouwd, wordt door het Europees Congres niet verboden vóór het jaar 20XX.

- Het recht op habeas corpus wordt niet opgeschort tenzij het noodzakelijk wordt geacht voor de openbare veiligheid in geval van opstand of een invasie.

- Het Europees Congres mag geen wet met terugwerkende kracht aannemen, noch een wet over de burgerlijke dood. Noch een wet aannemen die afbreuk doet aan contractuele verplichtingen of rechterlijke uitspraken van welke rechtbank dan ook.

Sectie 4 - Beperkingen voor de Verenigde Staten van Europa en hun staten

- Er zullen geen belastingen, imposten of accijnzen worden geheven op transnationale diensten en goederen tussen de Staten van de Verenigde Staten van Europa.

- Geen voorrang zal worden gegeven door enige verordening aan de handel of aan belasting in de zee- en luchthavens van de Staten van de Verenigde Staten van Europa; noch zullen schepen of vliegtuigen, op weg naar of afkomstig uit een Staat, verplicht worden een andere Staat binnen te varen, in te klaren of daar rechten te betalen.

- Geen enkele staat mag een wet met terugwerkende kracht of een wet op de burgerlijke dood aannemen. Noch een wet aannemen die afbreuk doet aan contractuele verplichtingen of rechterlijke uitspraken van welke rechtbank dan ook.

- Geen enkele staat zal zijn eigen munt uitgeven.

- Geen Staat zal, zonder toestemming van het Europese Congres, belastingen, imposten of accijnzen heffen op de in- of uitvoer van diensten en goederen, met uitzondering van hetgeen noodzakelijk kan zijn voor de uitvoering van inspecties bij in- en uitvoer. De netto-opbrengst van alle belastingen, imposten of accijnzen, door enige Staat op de in- en uitvoer geheven, zal ten goede komen aan de schatkist van de Verenigde Staten van Europa; alle desbetreffende voorschriften zullen worden herzien en gecontroleerd door het Europees Congres.

- Geen enkele Staat zal, zonder toestemming van het Europees Congres, een leger, een zeemacht of een luchtmacht hebben, een overeenkomst of verbond sluiten met een andere Staat van de Federatie of met een vreemde Staat, of een oorlog beginnen, tenzij hij daadwerkelijk wordt binnengevallen of geconfronteerd wordt met een onmiddellijke dreiging die uitstel onmogelijk maakt.

Sectie 5 - Beperkingen voor de Verenigde Staten van Europa[1]

- Er zal geen geld uit de schatkist worden geput dan voor het gebruik zoals bepaald door de federale wet; jaarlijks zal een overzicht van de financiën van de Verenigde Staten van Europa worden gepubliceerd.

- Geen adellijke titel zal door de Verenigde Staten van Europa worden verleend. Niemand die onder de Verenigde Staten van Europa een openbaar ambt of een vertrouwensambt bekleedt, aanvaardt zonder toestemming van het Europees Congres enig geschenk, emolument, ambt of titel van welke aard dan ook, van enige Koning, Prins of vreemde Staat.

- Al dan niet bezoldigde personeelsleden van de regering, van contractanten van de regering of van entiteiten die directe of indirecte financiering van de regering ontvangen, mogen geen voet op buitenlandse bodem zetten met het oog op vijandelijkheden of acties ter voorbereiding van vijandelijkheden, tenzij toegestaan door een oorlogsverklaring van het Congres.

- Geen enkele persoon of entiteit, levend, robot of digitaal, mag meer dan één dagloon van de gemiddelde arbeider in de VS bijdragen aan een persoon die zich verkiesbaar stelt in een bepaalde verkiezingscyclus, in geld, goederen, diensten of arbeid, betaald of onbetaald. Iedereen die een verkozen functie wil bekleden en meer dan dit bedrag in welke vorm dan ook aanvaardt, en iedereen die probeert deze wettelijke beperking op campagnebijdragen te omzeilen, zal levenslang worden uitgesloten van het bekleden van een functie en zal een gevangenisstraf van ten minste vijf jaar moeten uitzitten.

- Personen of entiteiten die de afgelopen vijf jaar rechtstreeks of onrechtstreeks fondsen, gunsten of contracten van de regering hebben ontvangen, mogen niet bijdragen aan een verkiezingscampagne op grond van de in lid 6 beschreven sancties. Bovendien wordt elke entiteit die deze beperking tracht te omzeilen, een boete opgelegd van vijf jaar van haar jaaromzet, betaalbaar bij veroordeling.

- Elke directe of indirecte bijdrage in geld, goederen, diensten of arbeid, betaald of onbetaald, aan een persoon die een verkiesbaar ambt nastreeft, moet binnen achtenveertig uur na ontvangst openbaar worden gemaakt. Op de bijdrage van elke entiteit moet de naam worden vermeld van de persoon of personen die verantwoordelijk zijn voor het beheer van de entiteit. Een entiteit die deze beperking tracht te omzeilen, krijgt een boete van vijf jaar op jaarbasis, te betalen bij veroordeling.

- Niemand mag meer dan één maand van het gemiddelde maandloon van een gemiddelde werknemer besteden aan zijn eigen campagne voor een verkozen ambt. Wie deze wettelijke beperking op campagnebijdragen wil omzeilen, wordt levenslang uitgesloten van het uitoefenen van een ambt en krijgt een minimumstraf van vijf jaar gevangenisstraf.

- Een overheidswerknemer mag gedurende een periode van tien jaar na het beëindigen van zijn overheidsfunctie gedurende de afgelopen vijf jaar geen functie aanvaarden bij een particuliere entiteit die overheidsfinanciering, gunsten of contracten heeft aanvaard.

- Elke instelling en elk overheidsorgaan en elke entiteit of persoon die direct of indirect overheidsfinanciering, gunsten of contracten heeft ontvangen, zal om de vier jaar aan een onafhankelijke audit worden onderworpen, en de resultaten van deze forensische audits zullen openbaar worden gemaakt op de datum waarop zij worden gepubliceerd. Elke entiteit die deze verplichting tracht te omzeilen of te ontduiken, krijgt een boete van vijf jaar, te betalen bij een veroordeling. Eenieder die deze eis tracht te omzeilen of te ontduiken, moet een gevangenisstraf van ten minste vijf jaar uitzitten.

[1] De clausules 3-9 van artikel III zijn toegevoegd door Leo Klinkers, overgenomen van Charles Hugh Smith, 10 verstandige amendementen op de grondwet van de VS, 21 februari 2019.

De bevoegdheden van het Congres betreffen zaken van nationaal belang. Bijvoorbeeld de munteenheid, federale belastingen, handelsbetrekkingen met andere landen, buitenlandse zaken en defensie. En een aantal andere - uitputtend opgesomde - zaken.

Elk wetsvoorstel komt dus van een van de Kamers en wordt eerst aan de president voorgelegd. Hij kan het ondertekenen of een met redenen omkleed veto uitspreken. In het laatste geval gaat het terug naar de betrokken Kamer voor heroverweging. Als die Kamer en de andere Kamer het voorstel vervolgens met een tweederde meerderheid goedkeuren, is de wet aangenomen.

Uitleg van deel 1

Hier kiezen wij voor een andere structuur dan die van de Amerikaanse grondwet. Het Amerikaanse artikel I van die grondwet telt tien afdelingen. Deze hebben zowel betrekking op de organisatie van het Congres als op zijn bevoegdheden. Wij vinden het beter deze twee onderwerpen te splitsen. Daarom hebben wij ons artikel II de titel "Organisatie van de wetgevende macht" gegeven, die vervolgens de afdelingen 1-6 omvat. Vervolgens behandelen wij de Afdelingen 7 t/m 10 in een nieuw Artikel III onder de titel "Bevoegdheden van de wetgevende macht". De afdelingen 7 t/m 10 van het Amerikaanse artikel I zijn dan in ons artikel III genummerd als de afdelingen 1-4.

Dus, beide kamers maken initiatiefwetten. Niet de president en de ministers van zijn kabinet. Zij treden zelfs niet op in de Kamers. Deze strikte scheiding van wetgevende en uitvoerende macht garandeert de autonomie van het Europees Congres in zijn kerntaak: het opstellen en definitief goedkeuren van federale wetten.

Afdeling 1 verleent aan het Huis der Burgers de exclusieve bevoegdheid om belastingwetten te maken. In tegenstelling tot wetgeving in algemene zin, heeft de Senaat die bevoegdheid dus niet. Wel kan de Eerste Kamer proberen die belastingwetten door amendementen te wijzigen. De reden om alleen het Huis van de Burgers bevoegd te verklaren om ter zake een initiatief te nemen, berust op de overweging dat het "tasten in de portemonnee van de burgers" uitsluitend en alleen ter beoordeling staat van de vertegenwoordigers van die burgers.

Het Huis van de Burgers beslist dus welk soort federale belasting zal worden geheven: inkomstenbelasting, vennootschapsbelasting, onroerende voorheffing, verkeersbelasting, vermogensbelasting, winstbelasting en/of belasting over de toegevoegde waarde. Of misschien laat het deze soorten belastingen over aan de jurisdictie van de Staten en creëert het slechts één nieuwe soort belasting onder de naam Federale belasting, op voorwaarde dat tegelijkertijd de belastingen van de Staten worden verlaagd of afgeschaft om te voorkomen dat deze Federale belasting ten koste van de Burgers wordt geheven. Meer zeggen wij hier niet over, omdat dit een onderwerp is voor de politiek gekozenen. Daarom spreken wij ons hier niet uit over het geschil betreffende de harmonisatie van de belastingen, bijvoorbeeld de vennootschapsbelasting.

In clausule 2 wordt de toepassing van de Lex Silencio Positivo, een regel van het Romeinse recht, is opmerkelijk: als de president zich niet binnen tien dagen uitspreekt, wordt het voorstel automatisch wet. Wijst de president het wetsvoorstel af, dan moet hij zijn afwijzing met redenen omkleden en het voorstel terugzenden naar de Kamer die het heeft opgesteld. Dit wordt het veto van de president genoemd. Het woord "veto" wordt overigens niet expliciet genoemd in de Amerikaanse grondwet. Het staat ook niet in ons artikel.

Op deze plaats lijkt het nuttig om kort in te gaan op een van de gevolgen van de Amerikaanse keuze om het principe van de trias politica te ondersteunen met een ingenieus systeem van checks and balances. In de praktijk leidt dit in de VS soms tot een situatie waarin een van de Kamers samen met de president een blokkade vormt om een begrotingscrisis op te lossen (fiscal cliff). Oppervlakkig gezien zou men dit kunnen toeschrijven aan een grondwettelijke systeemfout: als beide machten op hun grondwettelijke lijn staan, ontstaat er een impasse. En dat zou kunnen worden gezien als een fout van de Amerikaanse grondwet. Maar deze opvatting is onjuist als men teruggaat naar de belangrijkste reden voor de instelling van dit systeem van checks and balances: nooit meer mag iemand de absolute baas zijn over ieder ander. Dit dwingt alle betrokken partijen om, in geval van een eventuele impasse, de verantwoordelijkheid te tonen die de Burgers hun hebben gegeven. En dat is niet meer of minder dan ervoor zorgen dat de impasse wordt doorbroken. Het voortduren van zo'n trieste situatie is dus niet te wijten aan een systeemfout van de Amerikaanse grondwet, maar aan het onvermogen van de betrokken politici om verantwoordelijkheid te nemen voor het algemeen belang.

In het presidentiële systeem van de VS is dus geen van de drie takken - de wetgevende, de uitvoerende en de rechterlijke macht - de baas over de andere. Er is maar één baas: het volk. Het volk kan die macht op twee manieren tonen: in verkiezingen en in een referendum dat een beslissende oplossing biedt wanneer de drie takken van de regering in een impasse zijn geraakt. De referendumkwestie wordt besproken in 6.8.

Uitleg van deel 2

De limitatieve opsomming van de bevoegdheden van de federale overheid is een typisch kenmerk van het federale systeem: de staten mogen alles regelen wat niet uitdrukkelijk aan de federale overheid is toegewezen. Er is nauwkeurig vastgelegd dat de federale overheid zich niet mag mengen in aangelegenheden die tot het bevoegdhedencomplex van de staten behoren. Zie hier de bescherming van de soevereiniteit van de staten. En omgekeerd is ook vastgelegd in welk opzicht die staten zich niet met het federale gezag mogen bemoeien, tenzij met machtiging van het Congres.

Dit is precies een van de belangrijkste verschillen tussen intergouvernementalisme en een federatie: geen hiërarchie aan de top, gedeelde soevereine wetgevende macht van de federatie en haar samenstellende delen, de staten. Dus geen inmenging in het federale bestuursniveau en in dat van de staten. Dit is in tegenspraak met de populaire misvatting dat een federale staat een superstaat is die uiteenvalt en de soevereiniteit van de samenstellende staten opslokt. Quod non. In een federaal stelsel blijven de bevoegdheden van de staten en het federale orgaan gescheiden.

De limitatieve opsomming van de bevoegdheden van de wetgever is bedoeld om gemeenschappelijke belangen te regelen waarin de burgers of de staten niet kunnen voorzien. De essentie van de verticale machtsverdeling is dat burgers en staten een federale instantie vragen om een beperkt aantal gemeenschappelijke belangen (waarvoor zij ook bereid zijn te betalen) goed te behartigen, zonder dat deze federale instantie het recht heeft om aan te nemen dat zij dan ieders baas is. Alle andere bevoegdheden blijven bij de burgers en de staten, onaantastbaar voor de federale overheid. De Staten behouden hun eigen parlement, regering en rechterlijke macht voor wat niet aan de Verenigde Staten van Europa is toegewezen.

Deze afdeling 2 is onze versie van de zogenaamde "Kompetenz Katalog" die Duitsland voorstelde tijdens het Verdrag van Maastricht in 1992, en vele malen daarna, maar die steeds door andere EU-landen werd verworpen. Dit is een van de ernstige tekortkomingen van het intergouvernementele systeem.

Onze lijst is totaal verschillend van de uitputtende lijsten (meervoud) die wij in het Verdrag betreffende de werking van de Europese Unie met betrekking tot de Europese Unie aantreffen. Niet alleen zijn zij niet precies en werkelijk uitputtend, maar zij worden ook doorkruist door het oncontroleerbare subsidiariteitsbeginsel, de hiërarchische uitoefening van de bevoegdheden en de verdeling van de bevoegdheden: dit alles is een vloek in een echt federale tempel omdat het een inbreuk vormt op de soevereiniteit van de staten. Voor de goede orde: dit beginsel van de limitatieve opsomming van federale bevoegdheden is een van de grootste successen van de debatten in de Conventie van Philadelphia en werd binnen twee weken bereikt.

Dit lijkt een goede plaats om Frank Ankersmit, emeritus hoogleraar Geschiedenis van de Wijsbegeerte, te citeren. In het Nederlands Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2012, getiteld 'De Verenigde Staten van Europa', schrijft hij onder meer:

"Het heeft geen zin om op deze plaats in te gaan op de besluitvorming in Europa, en daarom volstaat het op te merken dat deze haaks staat op alles wat in de geschiedenis van de politieke filosofie over openbare besluitvorming is bedacht. Deze besluitvorming in Europa is volstrekt uniek in de geschiedenis - en dat is zeker niet in positieve zin bedoeld. Gezien de immense problemen van de Europese eenwording kan men dat begrijpen; maar het is en blijft een lelijke zaak. Meer in het bijzonder is dit besluitvormingsproces in feite de officiële codificatie van alle onzekerheden omtrent het uiteindelijke doel van de Europese eenwording. Het is alsof de Europese bestuurders deze onzekerheid opzettelijk hebben vertaald in een bestuursstructuur die er de organisatorische uitdrukking van is. Het is alsof zij het onvermogen van Europa om over zijn eigen schaduw heen te springen vroeg of laat onverbrekelijk hebben willen vastleggen in een bestuurlijke structuur die dit feitelijk onmogelijk zou maken."

Vergelijk dit met de reeds genoemde systeemfouten (zie hoofdstuk 3) van het Verdrag van Lissabon. Het is zo'n gebrekkig document (wetgevend, democratisch, organisatorisch, besluitvormend) dat vernieuwing alleen mogelijk is door er uit te stappen: 'step out of that box' en vermijd de valkuil om te proberen het systeem te verbeteren door dat gebrekkige Verdrag aan te passen. Het zit immers vol met systeemfouten. Elke nieuwe wijziging zal door deze fouten worden vergiftigd omdat ze er als het ware 'genetisch' zijn ingebrand.

Degenen die een leidende positie bekleden in het intergouvernementele systeem beseffen niet hoe destructief verkeerde wetgeving is voor een samenleving. Fundamentele kennis en begrip van de noodzaak van een doordachte constitutionele vormgeving als basis voor een goed functionerende samenleving ontbreken kennelijk. Onvoldoende kennis en moed om een wezenlijke bijdrage te leveren aan de totstandkoming van de Verenigde Staten van Europa.

Het aanvaarden van het Verdrag van Lissabon als basis voor het streven naar een verenigd Europa is naar onze mening een vorm van ongewenste relativering van het recht. Als een bagatellisering van de noodzaak om de constitutionele basis van de samenleving onder alle omstandigheden van een professioneel geformuleerde codificatie te voorzien. Ook al hebben delen van het recht, met name het bestuursrecht, een instrumentele functie gekregen (recht als instrument om politieke beleidsdoelen te bereiken), er zijn en blijven leerstukken van onvervreemdbaar, fundamenteel recht waar politiek noch beleid aan mag tornen. De "rechtsstaat" betekent dat niemand boven de wet staat. Maar dat heeft alleen betekenis als het maken van die wet gebeurt volgens onweerlegbare normen, niet vervuild door politieke folklore.

Dan nu ons ontwerp voor een federale grondwet. Essentiële toevoegingen ten opzichte van de Amerikaanse grondwet zijn:

- Clausule d, immigratiebeleid als een federale aangelegenheid en niet langer behorend tot een Europese lidstaat, maar met medewerking van de staten bij de handhaving van de federale regels, b.v. via hun diensten voor bijstand, onderwijs en politie.

- Clausule j, de basis voor een federale aanpak van een Europese digitale (elektronische) agenda plus de bestrijding van cybercriminaliteit.

- Clausule n voorziet in de oprichting van federale strijdkrachten, d.w.z. één Europees leger van landmacht, zeemacht en luchtmacht. Een bekend nationaal(istisch) gedreven twistpunt, maar als provinciale folklore onder een federale Grondwet niet de moeite van het aanvechten waard.

Deze afdeling 2 gaat dus over het belangrijkste aspect van een federatie: de verticale scheiding van bevoegdheden tussen de federatie enerzijds en de burgers en staten anderzijds. Wat het Europees Congres mag regelen staat er limitatief opgesomd. Dit betekent echter niet dat meteen duidelijk is uit hoeveel ministers de uitvoerende macht zou moeten of kunnen bestaan. Dus, voor welke beleidsterreinen zou er van meet af aan een minister met een eigen ministerie moeten zijn in de Verenigde Staten van Europa? Wij zullen hierop ingaan bij de organisatie van de uitvoerende macht.

Wat deze uitputtende lijst betreft, moet op drie punten worden gewezen.

In de eerste plaats merken wij op dat de Verenigde Staten van Europa logischerwijs ook bevoegd zijn om de hun toegekende bevoegdheden uit te oefenen, niet alleen binnen de Federatie maar ook daarbuiten, bijvoorbeeld door het sluiten van verdragen. Wij verbinden de bevoegdheden van de Federatie zowel aan haar binnenlands beleid als aan haar buitenlands beleid. Hetzelfde geldt voor de Staten die lid zijn van de Federatie. Hoe dit in zijn werk gaat, komt aan de orde in de organisatie van de uitvoerende macht.

Ten tweede moeten we wijzen op de laatste bevoegdheid van sectie 2, clausule o. In de tekst van de Amerikaanse grondwet staat: "Om alle wetten te maken die nodig en gepast zijn om de voorgaande bevoegdheden uit te voeren, en alle andere bevoegdheden die door deze grondwet aan de regering van de Verenigde Staten, of aan een departement of functionaris daarvan, zijn toegekend." Dit is de beroemde 'Necessary and Proper Clause': Het Congres kan alle wetten maken die het nodig acht. Maar als die niet onmiskenbaar voortvloeien uit de limitatieve reeks bevoegdheden krachtens hun artikel I, sectie 8 (ons artikel III, sectie 2) kan de president er zijn veto over uitspreken. Of het Hooggerechtshof kan ze ongrondwettig verklaren, de zogenaamde "Judicial Review". Zie hoofdstuk 10.

Ten derde, een ander belangrijk aspect. Het Amerikaanse Congres heeft in feite nog meer bevoegdheden dan die welke in zijn grondwet worden genoemd onder artikel I, sectie 8 (ons artikel III, sectie 2). We komen nu op het terrein van de zogenaamde "Implied Powers" (zie verder hoofdstuk 10): bevoegdheden die niet letterlijk in de Grondwet staan, maar die zijn afgeleid van het complex van bevoegdheden van de Amerikaanse Sectie 8.

Een van de belangrijkste wordt "Congressional Oversight" genoemd. Dit toezicht - voornamelijk georganiseerd via parlementaire commissies (zowel permanente als bijzondere), maar ook met andere instrumenten - betreft de algemene werking van de uitvoerende macht en de federale agentschappen. Het doel is de doeltreffendheid en efficiëntie te verhogen, de uitvoerende macht in overeenstemming te houden met haar onmiddellijke taak (uitvoering van wetten), verspilling, bureaucratie, fraude en corruptie op te sporen, burgerrechten en vrijheden te beschermen, enzovoort. Het is een alomvattend toezicht op de gehele beleidsuitvoering. Dit is overigens niet iets uit het recente verleden, het is ontstaan vanaf het ontstaan van de Grondwet en is een onbetwist onderdeel van het ingenieuze systeem van checks and balances.

Let wel, de Grondwet kent dit "Congressional Oversight" niet met zoveel woorden, maar het wordt verondersteld een onvervreemdbare uitbreiding te zijn van de wetgevende macht: als je bevoegd bent om wetten te maken, moet je ook bevoegd zijn om te controleren wat er gebeurt bij de uitvoering ervan. In een bestuurlijke cyclus is dat vanzelfsprekend.

Natuurlijk zijn er pogingen geweest om met een strikte interpretatie van de Amerikaanse grondwet aan te tonen dat deze vorm van "Implied Powers" niet in overeenstemming is met de grondwet. Het Hooggerechtshof van de VS heeft deze bewering echter altijd verworpen. Dit is in lijn met de visie van president Woodrow Wilson, die dit parlementaire toezicht net zo belangrijk vond als het maken van wetten: "Even belangrijk als wetgeving is waakzaam toezicht op de administratie." Dit alles in de wetenschap dat de grondwet van de VS in artikel I, sectie 9, de grenzen bepaalt waarbinnen het Congres van de VS de beperkende bevoegdheden van hun sectie 8 mag uitoefenen.

Wij willen de aandacht vestigen op enkele specifieke clausules van onze gewijzigde Afdeling 2.

Ten eerste, clausule a, de bevoegdheid om belastingen en dergelijke te heffen. Dit is in Amerika nodig om de schulden te betalen en "voor de gemeenschappelijke verdediging en het algemeen welzijn van de Verenigde Staten". Wij hebben de woorden tussen aanhalingstekens vervangen door "noodzakelijk voor de vervulling van de in de Preambule neergelegde waarborg". Naar onze mening moet het genereren van eigen inkomsten van de federale overheid verder gaan dan de betaling van de schulden van de federatie en de financiering van de uitgaven voor defensie en het algemeen welzijn. Naast de expliciete verwijzing naar het kunnen betalen van de eigen schulden, achten wij het van belang dat hier een duidelijk verband wordt gelegd met de garantie in de Preambule. Met andere woorden, dat die belasting er ook is om de uitgaven te betalen "van vrijheid, orde, veiligheid, geluk, rechtvaardigheid, verdediging tegen vijanden van de Federatie, bescherming van het milieu, alsmede aanvaarding en verdraagzaamheid van de verscheidenheid van culturen, geloofsovertuigingen, levenswijzen en talen van allen die wonen en zullen wonen op het grondgebied dat onder de rechtsmacht van de Federatie valt".

Clausule c wordt in de Amerikaanse grondwet de "Commerce Clause" genoemd. Voor de Verenigde Staten van Europa zal de toepassing van deze bepaling - mede in het licht van het sluiten van handelsverdragen - van essentieel belang zijn voor de financieel-economische positie van Europa. Zaken als een Fiscale Unie en de internationalisering van de euro (zie paragraaf 3) spelen daarbij een belangrijke ondersteunende rol.

Uitleg van deel 3

Sectie 3 is gewijd aan principiële grenzen aan de federale bevoegdheden die in Sectie 2 aan het Congres zijn toegekend om individuen te beschermen. Deze beknopte Sectie 3 over individuele rechten is voldoende in deze ontwerp-Grondwet. Meer is niet nodig. In sectie I, clausule 3 van het ontwerp staat immers dat de Verenigde Staten van Europa het Handvest van de grondrechten van de EU onderschrijven (met uitzondering van het onwerkzame subsidiariteitsbeginsel[1]) en treedt toe tot het Verdrag tot bescherming van de rechten van de mens en de fundamentele vrijheden, dat in het kader van de Raad van Europa is gesloten.

De eerste clausule van sectie 3 geeft de staten het recht om nog een paar jaar hun eigen vreemdelingenbeleid te voeren. Vanaf het nog niet nader genoemde jaar 20XX zal dit het federale immigratiebeleid zijn. En daarmee zal de Federatie van Europa zich profileren als een Federatie die buitenlanders onder bepaalde voorwaarden welkom heet, in plaats van gebruik te maken van bureaucratische en vijandige politiemechanismen en juridische constructies gericht op verdediging om burgers uit andere werelddelen buiten de Federatie te houden, of te verbannen. De Verenigde Staten van Europa kunnen nog tientallen miljoenen actieve, ondernemende volkeren gebruiken om hun culturele diversiteit te verrijken, hun economie te versterken en hun krimpende bevolking het hoofd te bieden. Dit vereist een beleid[2] die immigratie organiseert ten voordele van de federatie en de immigrant. Europese beleidsmakers kunnen inspiratie putten uit het beleid van federaties als Australië, Canada en de Verenigde Staten.

Uitleg van Sectie 4

Volgens de clausules 1 en 2 van deze afdeling mogen noch de Staten van de Federatie, noch de Federatie zelf, voorschriften invoeren of handhaven die de economische eenheid van de Federatie beperken of doorkruisen. Ook hier geldt dat de bevoegdheden die in artikel III, lid 2, van de Grondwet niet uitdrukkelijk aan het Congres zijn toegekend, berusten bij de burgers en de staten. Dit is de andere kant van de medaille die "verticale scheiding der machten" wordt genoemd. Niettemin werd het destijds in Amerika nuttig en noodzakelijk geacht om niet alleen in hun Artikel I, Sectie 9 grenzen aan het Congres te stellen, maar ook om de Staten eraan te herinneren dat hun bevoegdheden niet onbeperkt zijn. Daartoe is in hun artikel I, sectie 10 (ons artikel III, sectie 4) bepaald wat de staten niet mogen doen.

Clausule 3 legt aan de wetgevende bevoegdheid van de staten dezelfde beperking op als die van de federatie, vervat in artikel 3, lid 3, teneinde de rechtszekerheid te handhaven, de uitoefening van de rechterlijke bevoegdheid niet aan te tasten en de rechten van de burgers die van kracht zijn of worden gehandhaafd, te vrijwaren. Het is ook van belang, een onderwerp dat vaak door het Hooggerechtshof van de VS aan de orde is gesteld, dat staten geen wetgeving mogen uitvaardigen om contractuele verplichtingen terzijde te schuiven. Rechtszekerheid voor contractanten en procespartijen is van een hogere orde dan de bevoegdheid om een contract of een rechterlijke beslissing bij wet onverbindend te verklaren.

In clausule 4 is de bepaling dat geen van de lidstaten van de federatie zijn eigen munteenheid mag creëren (ontleend aan James Madison's Federalist Paper nr. 44) een duidelijke waarschuwing aan sommige EU-lidstaten die overwegen terug te keren naar hun eigen voormalige nationale munteenheden. Niettemin mogen de staten obligaties en andere schuldinstrumenten uitgeven om hun tekorten te financieren. Met andere woorden, wij stellen voor een financieel stelsel te creëren dat vergelijkbaar is met dat van de VS.

Volgens clausule 5 vallen in- en uitvoerrechten niet onder de bevoegdheid van de staten, tenzij zij daartoe gemachtigd zijn. Zij mogen echter wel heffingen opleggen voor de kosten die zij maken in verband met de controle op in- en uitvoer. De netto-opbrengst van de toegestane heffingen moet in de kas van de Federatie vloeien. Deze kwestie zal waarschijnlijk hoog op de agenda staan van de eerder aanbevolen zes senatoren (zonder stemrecht) die door de ACS-landen naar de Europese Senaat zijn afgevaardigd.

In clausule 6 wordt nog eens benadrukt dat defensie een federale taak is. Met dien verstande dat het Europees Congres kan besluiten dat een lidstaat een deel van dat federale leger op zijn grondgebied moet huisvesten en paraat moet houden om in geval van nood op te treden.

Toelichting bij Afdeling 5

In deze afdeling 5 hebben wij een aantal aanvullende regels opgenomen ter bestrijding van politieke corruptie[3]. Omdat er in Amerika gigantische sommen geld worden uitgegeven aan verkiezingscampagnes, is er een gezegde: "Geld is de zuurstof van de Amerikaanse politiek". In onze federale grondwet voor de Verenigde Staten van Europa bevat artikel III, lid 5, clausules die het adagium rechtvaardigen: "Geld mag niet de zuurstof van de Europese politiek zijn".

Dit is onze beschrijving van de artikelen I-III van de Verenigde Staten van Europa. Wij hebben ons zo dicht mogelijk bij de tekst van de Amerikaanse grondwet gehouden. Het is daarom denkbaar dat woorden of zinsneden - die van vitaal belang zijn voor een federaal Europa - abusievelijk ontbreken of onjuist zijn geformuleerd. Of dat wij hier dingen regelen die in de beoogde Europese federale context niet nodig zijn. Daarom staat deze tekst - net als de rest van onze ontwerp-grondwet - open voor aanvulling en verbetering door de Conventie van de burgers.

De volgende artikelen IV-X zijn deels ontleend aan de oorspronkelijke Amerikaanse grondwet zelf, deels aangevuld en verbeterd met teksten uit de amendementen die er vervolgens door het Congres aan zijn toegevoegd. Ook hier veroorloven wij ons de leesbaarheid van de structuur van de Amerikaanse grondwet te verbeteren door de organisatie van de uitvoerende macht te scheiden van de duur en de vacature van het (vice-)presidentschap.

[1] Het subsidiariteitsbeginsel wordt evenmin in de preambule genoemd omdat subsidiariteit samenvalt met federalisme. Dit is reeds uiteengezet.

[2] Dat beleid zal afscheid nemen van Frontex, het Europees agentschap voor de buitengrenzen en de kustwacht. De manier waarop de Europese Unie heeft toegestaan dat dit agentschap zich qua bevoegdheden, personeel, procedures en wapens heeft ontwikkeld tot een verdedigingsmechanisme zonder democratische controle en zonder toetsing door mensenrechtenorganisaties, en aldus het speelterrein van industriële lobbyisten is geworden, zou wel eens kunnen uitgroeien tot de grootste anti-humanitaire misdaad van de 21e eeuw.

[3] De clausules 3-9 van artikel III zijn toegevoegd door Leo Klinkers, overgenomen uit Charles Hugh Smith, '10 Common- Sense Amendments to the US Constitution', 21 februari 2019.

Artikel III... Bevoegdheden van de wetgevende macht

Sectie 1 - Legislative procedure

- Both Houses have the power to initiate laws. They may appoint bicameral commissions with the task to prepare joint proposal of laws or to solve conflicts between both Houses.

- The laws of both Houses must adhere to principles of inclusiveness, deliberative decision-making, and representativeness in the sense of respecting and protecting minority positions within majority decisions, with resolute wisdom to avoid oligarchic decision-making processes.

- The House of the Citizens has the power to initiate legislation affecting the federal budget of the European Federal Union. The House of the States has the power - as is the case with other legislative proposals by the House of the Citizens - to propose amendments in order to adjust legislation affecting the federal budget.

- Elk wetsontwerp wordt naar het andere Huis gestuurd. Als de andere Kamer het wetsontwerp goedkeurt, wordt het wet. Indien de andere Kamer het wetsontwerp niet goedkeurt, wordt een tweekamercommissie gevormd - of wordt een reeds bestaande tweekamercommissie benoemd - om te bemiddelen en tot een oplossing te komen. Indien deze bemiddeling een akkoord of een voorstel van wet oplevert, is daarvoor de meerderheid van beide Kamers vereist.

- Elke bestelling of resolution, other than a draft law, requiring the consent of both Houses – except for decisions with respect to adjournment – are presented to the President and need his/her approval before they will gain legal effect. If the President disapproves, this matter will nevertheless have legal effect if two thirds of both Houses approve.

Section 2 - The Common European Interests

- Het Europees Congres is belast met de behartiging van de volgende gemeenschappelijke Europese belangen:

- (a) The livability of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies against existential threats to the safety of the European Federal Union, its States and Territories and its Citizens, be they natural, technological, economic or of another nature or concerning the societal peace.

(b) The financial stability of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies to secure and safe the financial system of the Federation.

(c) The internal and external security of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on defence, intelligence and policing of the Federation.

(d) The economy of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on the welfare and prosperity of the Federation.

(e) The science and education of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on the level of wisdom and knowledge of the Federation.

(f) The social and cultural ties of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on preserving established social and cultural foundations of Europe.

(g) The immigration in, including refugees, and the emigration out of the European Federal Union, by regulating immigration policies on access, safety, housing, work and social security, and emigration policies on leaving the Federation.

(h) The foreign affairs of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on promoting the values and norms of the European Federal Union outside the Federation itself. - The Federation and the Member States have shared sovereignty concerning those Common European Interests. The European Congress derives its powers in relation to these Common European Interests from powers that the Member States of the Federation entrust to the federal body through a vertical separation of powers. This implies that new circumstances may lead to a decision by the European Congress to increase or decrease the list of European Common Interests.

- Appendix III A, being integral part of this Constitution but not subject to the constitutional amendment procedure, regulates the way the Member States decide which powers to entrust to the federal body. It also regulates the influence of the Citizens on that process.

Section 3 – Constraints for the European Federal Union and its States

- Geen enkele staat zal op staatsniveau beleidsmaatregelen of acties invoeren die de veiligheid van zijn eigen burgers, of die van burgers van andere lidstaten, in gevaar kunnen brengen.

- No taxes, imposts or excises will be levied on transnational services and goods between the States of the European Federal Union.

- No preference will be given through any regulation to commerce or to tax in the seaports, air ports or spaceports of the States of the European Federal Union; nor will vessels or aircrafts bound to, or from one State, be obliged to enter, clear, or pay duties in another State.

- Geen enkele staat mag een wet met terugwerkende kracht aannemen of de doodstraf in ere herstellen. Noch een wet aannemen die afbreuk doet aan contractuele verplichtingen of rechterlijke uitspraken van welke rechtbank dan ook.

- Geen enkele staat zal zijn eigen munt uitgeven.

- No State will, without the consent of the European Congress, impose any tax, impost or excise on the import or export of services and goods, except for what may be necessary for executing inspections of import and export. The net yield of all taxes, imposts, or excises, imposed by any State on import and export, will be for the use of the Treasury of the European Federal Union; all related regulations will be subject to the revision and control by the European Congress.

- No State will have military capabilities under its control, enter any security(-related) agreement or covenant with another State of the Federation or with a foreign State, and can only employ military capabilities out of self-defense against external violence when an imminent threat requires this, and only for the duration that the Federation cannot fulfil this obligation. The military capabilities that are used in the above-mentioned situation are capabilities that are stationed on the State’s territory as part of that federal army.

Section 4 – Constraints for the European Federal Union

- No money shall be drawn from the Treasury but for the use as determined by federal law; a statement on the finances of the European Federal Union zal jaarlijks worden gepubliceerd.

- No title of nobility will be granted by the European Federal Union. No person who under the European Federal Union holds a public or a trust office accepts without the consent of the European Congress any present, emolument, office, or title of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince or foreign State.

- Al dan niet bezoldigde personeelsleden van de regering, van contractanten van de regering of van entiteiten die directe of indirecte financiering van de regering ontvangen, mogen geen voet op buitenlandse bodem zetten met het oog op vijandelijkheden of acties ter voorbereiding van vijandelijkheden, tenzij toegestaan door een oorlogsverklaring van het Congres.

- No person or entity, whether living, robotic or digital, may contribute more than one day's wages of the average laborer to a person seeking elected office in a particular election cycle, in currency, goods, services or labor, whether paid or unpaid. Anyone seeking an elected position that accepts more than this amount in any form, and anyone who seeks to circumvent this statutory limit on campaign contributions, will be barred from holding office for life and will serve a minimum term of imprisonment of five years.

- No person or entity that has directly or indirectly received funds, favors, or contracts from the government during the last five years may contribute to an election campaign under the sanctions described in clause 6. In addition, any entity seeking to circumvent this limitation shall be fined five years of its annual turnover, payable on conviction.

- Elke directe of indirecte bijdrage in geld, goederen, diensten of arbeid, betaald of onbetaald, aan een persoon die een verkiesbaar ambt nastreeft, moet binnen achtenveertig uur na ontvangst openbaar worden gemaakt. Op de bijdrage van elke entiteit moet de naam worden vermeld van de persoon of personen die verantwoordelijk zijn voor het beheer van de entiteit. Een entiteit die deze beperking tracht te omzeilen, krijgt een boete van vijf jaar op jaarbasis, te betalen bij veroordeling.

- Niemand mag meer dan één maand van het gemiddelde maandloon van een gemiddelde werknemer besteden aan zijn eigen campagne voor een verkozen ambt. Wie deze wettelijke beperking op campagnebijdragen wil omzeilen, wordt levenslang uitgesloten van het uitoefenen van een ambt en krijgt een minimumstraf van vijf jaar gevangenisstraf.

- Een overheidswerknemer mag gedurende een periode van tien jaar na het beëindigen van zijn overheidsfunctie gedurende de afgelopen vijf jaar geen functie aanvaarden bij een particuliere entiteit die overheidsfinanciering, gunsten of contracten heeft aanvaard.

- Elke instelling en elk overheidsorgaan en elke entiteit of persoon die direct of indirect overheidsfinanciering, gunsten of contracten heeft ontvangen, zal om de vier jaar aan een onafhankelijke audit worden onderworpen, en de resultaten van deze forensische audits zullen openbaar worden gemaakt op de datum waarop zij worden gepubliceerd. Elke entiteit die deze verplichting tracht te omzeilen of te ontduiken, krijgt een boete van vijf jaar, te betalen bij een veroordeling. Eenieder die deze eis tracht te omzeilen of te ontduiken, moet een gevangenisstraf van ten minste vijf jaar uitzitten.

Uitleg van deel 1

Clausule 1 entitles both Houses of the European Congress to make initiative laws. Not the President and the Ministers of his Cabinet. These executives do not even act in the Houses. This strict separation of legislative and executive power guarantees the autonomy of the European Congress in its core task: the drafting and final approval of federal laws.

Clausule 2 is a rather revolutionary text. Laws - with commandments and prohibitions - are the strongest instrument by which a government determines the behavioural alternatives of its Citizens. Citizens who believe that laws do not sufficiently consider the requirement of inclusiveness, deliberative decision-making, and representativeness in the sense of respecting and protecting minority positions within majority decisions, with resolute wisdom avoiding oligarchic decision-making processes can challenge this up to the highest court. The Federal Court of Justice has the power to test laws against the Constitution. In this Clause 2, therefore, lies a fundamental aspect of direct democracy: citizens have the right to challenge the correctness of a law before the highest court.

Clausule 3 gives the exclusive power to the House of the Citizens to make tax laws. Unlike legislation in the general sense, the House of the States therefore does not have that power. However, that House may try to change those tax laws through amendments. The reason for declaring only the House of the Citizens competent to take an initiative in this regard is based on the consideration that 'groping in the purse of the citizens' is solely and exclusively at the discretion of the delegates of those Citizens.

The House of the Citizens thus decides what type of federal taxation will take place: income tax, corporation tax, property tax, road tax, wealth tax, profits tax and/or value added tax. Or perhaps it will leave those types of tax to the jurisdiction of the States and creates only one new type of tax under the name Federal Tax, provided that States' taxes are simultaneously reduced or abolished to prevent this Federal Tax from being imposed at the expense of the Citizens. The Constitution says no more about this because it is a subject for the politically elected.

Clausule 4 excludes the President's involvement in the legislative process of both Houses. The US Constitution gives the President the power to veto a draft law, but then a complicated process follows between the President and both Houses to agree or disagree. We do not consider it desirable for the President, as leader of the Executive Branch, to participate in law making, nor in interfering in a possible dispute between the two Houses. We provide the establishment of a mediating bicameral commission in case both Houses cannot work it out together.

Clausule 5 gives the President a say in legislative matters of a lower level than a law.

Uitleg van deel 2

If one sees the Preamble as the soul of the Constitution, then Section 2 of Article III is its heart. It mixes procedural provisions with substantive issues and the way they are to be dealt with partly by the Federation and partly by the Member States.

The end-means relationships of the Constitution

Building a federation is mainly a matter of structure and procedures. It is not about substantive policy. There is no such thing as federalist policy, for example, in the sense of federalist agricultural policy. There are, however, the policies of the federation. But their content is not determined by the fact that it has a federal form of organisation but by the political views and decisions of the members of the House of the Citizens, of the States and of the Federal Executive. The Federation itself has no political colour. It is not left-wing; it is not right-wing, is neither progressive nor conservative. It is a safe house for all European Citizens, regardless their political, social, religious belief. A structure with procedures and guarantees that are geared as much as possible towards taking care of Common European Interests. In other words, interests that individual Member States can no longer take care of on their own.

Section 2 shows the list Common European Interests in relation to substantive subjects for which the Federal Authority needs powers to look after those interests. Because this federation is built on the principles of centripetal federalizing (by building from the bottom up the parts create the whole) the Member States shall determine for which Common European Interests they are entrusting which powers to the federation. This is the most important condition for preventing the federation from developing into a superstate. Federations that are built top down (centrifugal federalisation: a central government creates parts) have the characteristic that there will always be centralist aspects in the federation, with the risk of weakening the classical federal structure that aims to ensure that the parts always remain autonomous, independent, and sovereign.

Thus, the powers of the federal body come from the Member States, not in the sense of transferring or conferring, but in the sense of entrusting: the Member States make some of their powers dormant, as it were, so that the Federation can work with them to realise the Common European Interests. That is the socalled vertical separation of powers between the Member States and the Federal Authority, leading to shared sovereignty between the two.[1]

[1] The vertical separation of powers is the same as establishing subsidiarity. In other words, nowhere in a well-designed federal constitution is there a sentence that points to the principle of subsidiarity for the simple reason that the concepts of ‘vertical separation of powers’ and ‘subsidiarity’ coincide. See for more information the paragraphs 4.2.5, 4.2.8, 5.2, 5.3.2, 5.4 of the aforementioned Toolkit: https://www.faef.eu/wp-content/uploads/Constitutional-Toolkit.pdf.

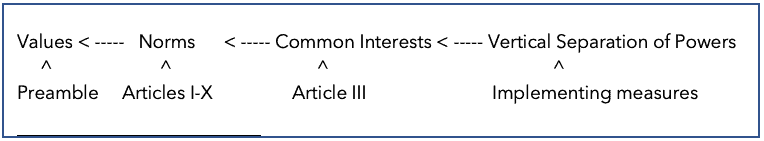

This requires a return to the passage on ‘Values and Interests’ in the General Observations of the Explanation to the Preamble. The Preamble to a federal Constitution is about values. The values are the objectives to be achieved through the deployment of Articles I to X. These articles contain the norms – read means – by which the values – read objectives – must be realised. The composition of a Constitution is thus a balanced relationship between values and norms or – in other words – between ends and means.

Interests on the other hand – better the Common European Interests of Europe, to be taken care of by the Federal Authority – are part of a second ends–means relationship. They are the means to realize the norms. And they are cared for and secured through the Vertical Separation of Powers between the Federal body and the Member States. So, that is a third means to end relationship.

Note that these three ends–means relationships are part of the ingenious system of checks and balances and require such attention that the ends are clear, that the means are clear and that the means can realise the ends. The arrows in the diagram – from right to left - show the means to end relations:

The FAEF Citizens’ Convention started the process of improving a provisional Constitution text with the perception that there are Values and Common European Interests; and that we can achieve (much) more through cooperation. Realization of these Common Interests are the objectives of forms of cooperation between the Member States and a Federal Authority. By expanding the scope, scale, and depth of the collaboration, it becomes possible to define those Common Interests in terms of means to fulfill the Norms and the Norms to fulfill the Values. These Values are understood as the foundation of the Federation, and as the ultimate objectives to be achieved. They have become the objectives in terms of the ‘what’ and indicate the desired direction (of development) for the Federation.

The Articles I - X concern principles for the organization of the Federation (structure and process) - the ‘how’ - and reflect (must be consistent with) the Values. The Articles can be considered Norms. i.e. rules and expectations (of ‘behavior’) that can be enforced. They are the means to fulfill the Values.

The Common Interests are the ‘where’. They can be considered ‘result areas’ that are established with a centripetal approach to federalization (bottom-up, minimalistic/cautious approach). These result areas are the more concrete issues/challenges where the Federation can provide added value for the Member States and the Citizens of the federation. The ‘field of activity’ of the Federal Authority is defined through the Common European Interests, that are identified by the Member States and its Citizens.

The Vertical Separation of Powers defines the content, the depth and the scope of the Common European Interests and is the beginning of the series of goal-means relationships. Anything that goes well - or perhaps not well - in the process of the vertical separation of powers by which Member States entrust powers to the Federal body will positively or negatively affect the meaning and value of the Common Interests. That, in turn, will affect the quality of the Norms and, in turn, that will affect the quality of achieving the Values. Thus, the success of the vertical separation in a good cooperative effort ultimately determines the success of what the Federation aims to achieve with the Values of the Preamble.

The Clauses of Section 2

Clausule 1 lists the Common European Interests. This is the fulcrum of a federal Constitution. The only reason to make a centripetal federation is that States realise that they can no longer look after some interests on their own. They then jointly create a Federal body and ask that body to look after a small set of common interests on their behalf and of their Citizens.

Clausule 1 lists the name of the Common European Interests. This gives a good idea of what these interests mean. For a better idea of their content, see Appendix III A. The Appendix describes the procedure for the vertical separation of powers which gives indications of the subjects of policies that are entrusted to the care of the Federal authority.

Clausule 2 explains what a centripetal federation is: the parts create a whole, a centre, which is empowered by the parts to look after common interests that individual States can no longer look after on their own. Although the list of Common European Interests is exhaustive, Clause 2 offers a window for increasing or decreasing it if new circumstances warrant. Naturally, this must be done via the procedure of Appendix III A and of the procedure to amend the Constitution. New circumstances can be: a new insight in the meaning of the values and norms of the constitution; a new insight in the meaning of Common European Interests that affect at least three states and have the potential to escalate to other states; the realization that the scale of new circumstances requires a uniform, efficient federal response.

Clausule 3 refers to Appendix III A that regulates the procedure of the vertical separation of powers. See the end of this Explanation on Article III.

More powers than the ones in Section 2

It is to be expected that the practice of the European Federal Union will show that the Houses of the European Congress - just like those of the US Constitution - feel that they do not have enough powers with the exhaustive Common European Interests mentioned in Section 2. A system of 'additional powers' will undoubtedly develop. An expansion of the complex of powers of both Houses that may be at odds with the intentions of the Constitution. One should think here of the following - potential - developments.

One of the most important is called 'Congressional Oversight'. This oversight - organised mainly through parliamentary committees (both standing and special), but also with other instruments - concerns the overall functioning of the Executive branch and Federal Agencies. The aim is to increase effectiveness and efficiency, to keep the executive in line with its immediate task (execution of laws), to detect waste, bureaucracy, fraud and corruption, protection of civil rights and freedoms, and so on. It is a comprehensive monitoring of the entire policy implementation. This, by the way, is not something of the recent past in the US. It arose from the inception of the Constitution and is an undisputed part of the ingenious system of checks and balances. It will undoubtedly develop in the same way in Europe.

The Constitution does not know this 'Congressional Oversight' in so many words, but it is supposed to be an inalienable extension of the legislative power: if you are authorised to make laws, you must also be authorised to control what happens in their implementation. It is self-evident in an administrative cycle. Of course, there have been attempts to demonstrate with a strict interpretation of the US Constitution that this form of 'Implied Powers' is not in accordance with the Constitution. However, the US Supreme Court has always rejected this claim. This is in line with the vision of President Woodrow Wilson, who saw this parliamentary oversight as being just as important as making laws: "Quite as important as legislation is vigilant oversight of administration."[1]

[1] For more information on these issues, see Chapter 10 of the aforementioned Toolkit: https://www.faef.eu/wp-content/uploads/Constitutional-Toolkit.pdf.

Explanation of Section 3

Clause 1 restrains policies and actions that may be crushing for biodiversity or that, for example, polluting energy companies are opened or remain open in violation of climate agreements. This ban must make a positive contribution to energy and food availability and security.

According to Clauses 2 en 3 of this Section, neither the States of the Federation, nor the Federation itself, may introduce or maintain regulations which restrict or interfere with the economic unity of the Federation. Again, powers not expressly assigned to Congress by the Constitution in Article III, Section 2 rest with the Citizens and the States. This is the other side of the coin called 'vertical separation of powers'. Nevertheless, in America it was considered useful and necessary at the time not only to place limits on Congress in their Article I, Section 9, but also to remind the States that their powers are not unlimited. To this end, their Article I, Section 10 - our Article III, Section 3 - stipulates what the States may not do.

Clausule 4 imposes the same limitation on the legislative power of the States as that of the Federation in order to maintain legal certainty, not to affect the exercise of judicial power and to safeguard rights of Citizens in force or enforced. It is also important, a subject that has often been addressed by the US Supreme Court, that States may not legislate to override contractual obligations. Legal certainty for contractors and litigants is of a higher order than the power to declare a contract or a court decision ineffective by law.

In Clausule 5, the provision that none of the member States of the Federation may create its own currency (taken from James Madison's Federalist Paper No 44) is a clear warning to some EU Member States considering returning to their own former national currencies. Nevertheless, states are allowed to issue bonds and other debt instruments to finance their deficit spending. In other words, we are proposing to create a financial system similar to that of the USA.

Clausule 6 states that export and import duties are not within the competence of the States unless they are authorised to do so. They may, however, charge for the expenses they incur in connection with the control of imports and exports. The net proceeds of permitted levies must fall into the coffers of the Federation. This matter is likely to have a high place on the agenda of the previously recommended six delegates of the House of the States (without voting rights) delegated by the ACP countries to the European House of the States.

Clausule 7 emphasizes once again that defence is a federal task. On the understanding that the European Congress may decide that a Member State shall accommodate on its territory a part of that federal army and keep it ready to act in case of emergency.

Uitleg van deel 4

In this Section 5 we have included a number of additional rules to combat political corruption. Because gigantic sums of money are spent on election campaigns in America, there is a saying: "Money is the oxygen of American politics". In our federal constitution for the United States of Europe, Article III, Section 5 contains Clauses justifying the adage: 'Money should not be the oxygen of European politics'.

Appendix III A - The procedure for the vertical separation of powers

By ratifying the Constitution, the Citizens adopt the limitative and exhaustive list of the Common European Interests. The question, however, is: how can one properly determine which powers are necessarily needed to enable the Federal Authority to do its job? For that, a procedure is needed. A procedure of debate and negotiation within which the Citizens (direct democracy) and the States play a prominent role. For this purpose, Clause 3 refers to Appendix III A which is an integral and therefore mandatory part of the Constitution, but for any future adjustment it is not subject to the amendment rules of the Constitution.

If the Constitution is ratified by enough Citizens to establish the Federation

the limitative and exhaustive list of the Common European Interests will be established. The meaning of this is: the Citizens have spoken; that list is non-negotiable during the debate and negotiation necessary to determine which powers should be entrusted – by means of that vertical separation of powers - to the Federal Authority, to enable the Federation taking care of the Common European Interests.

Let us repeat once again that the Member States retain their sovereignty in the sense that they do not transfer or confer parts of their sovereignty to the federal body and would thus lose those sovereignty. What they are doing is entrusting some of their powers to the federal body because that body can look after Common European Interests better than the Member States themselves. Thus, the Member States make their relevant powers dormant. The effect is shared sovereignty.

The vertical separation of powers will always be a matter of debate and will sometimes require adjustment. That is why the outcome of the debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers will be another Appendix to the Constitution: Appendix III B. The Appendix III A on the procedure of the process of the vertical separation of powers and the future Appendix III B, containing the result of that procedure, are integral parts of the Constitution but might be adjusted during the years without being subjected to the constitutional amendment procedure. This is to prevent that any necessary adjustments of the vertical separation will force to amend the Constitution itself.

On the basis of three principles, the founding fathers of this Constitution lay down the following procedure for determining the vertical separation of powers.

Principle 1 – from bottom to top

It would be a severe system error to arrange the allocation of powers from top to bottom. Wherever possible in the construction of a federal state, one should always work from the bottom up. That is a ‘commandment’ of the centripetal way on which this federal Constitution is based. This requires asking the Member States which parts of their complex of competences they wish to make dormant, so that the federal body can dispose of them to take care of the Common European Interests.

One must be careful not to think in terms of decentralization. Decentralization is ‘moving from top to bottom’: the center shares parts of its powers with lower authorities. This does happen in federal states that are centrifugally built: a centre creates parts. But the effect of such a course of action is that there will always remain unitary/centralist aspects. If countries such as Spain and the United Kingdom were to decide to further decentralize their already existing devolved autonomous regions into parts of a federal state, they would run the risk of creating a relatively imperfect federal state as well.

Principle 2 – debate and negotiation on Common European Interests

If the electorates of some European states ratify the Constitution by a majority, and if their parliaments follow the will of their people, the debate and negotiation on the powers that the Member States entrust to the Federation starts. This process is as follows:

a) Intern beraad van de afzonderlijke lidstaten

Each Member State has two months to prepare a document in which it puts forward proposals on the powers it wishes to entrust to the Federal body. In total, they draft one document for each Common European Interest. In doing so, they give an insight into the way in which they think the Federal body should be vested with substantive powers and material resources. A Protocol establishes the requirements that the documents must meet in order to be considered, among which the organization of the way Citizens participate in that process (direct democracy). The central requirement is that they must deal with the representation of Common European Interests that a Member State cannot (or can no longer) represent in an optimal manner itself.

b) Samenvoeging van de documenten

Under the leadership of FAEF, a Transition Committee is created beforehand to regulate the transition from the treaty-based to the federal system. This is where the Citizens come in as well: direct democracy. Led by FAEF, that Committee consists of (a) non-political Experts on the Common European Interests and (b) non-political Citizens. Point (a) is required for expertise. Point (b) is required to prevent the deliberation and decision-making on the vertical separation of powers from degenerating – as has been the case in the treaty-based intergovernmental EU-system since 1951 – into nation-state advocacy. The Transition Committee aggregates the documents of the Member States into a total sum of powers to be vertically separated, and the substantive and material consequences. Two months are available for this.

c) Definitieve besluitvorming

The aggregated document is the agenda for a one week deliberation on each Common European Interest. Under the leadership of the Transition Committee, final decisions are taken on the best balanced allocation of powers from the Member States to the Federal body. This final document will be an integral Appendix III B of the constitution. After its implementation in the federal system practice will show when, why and how Appendix III A on the procedure of the vertical separation of powers needs improvements, so that the Appendix III B on the result of that procedure must undergo improvements as well.

d) Het begin van de opbouw van het federale Europa

The result of c) marks the beginning of the building of the federal Europe. Guided by a Transition Committee of Citizens, the Member States determine concretely how the federal body with a limited number of entrusted powers of the states should represent a limited amount of Common European Interests. It marks a barrier between the tasks of the federation and the fields in which the Member States remain fully autonomous and the federation cannot become a superstate.

Principle 3 - Debatable and negotiable subjects

Taking from the limitative and exhaustive list of Common European Interests of Section 2, Principle 3 contains non-exhaustive examples of topics on which the debate and negotiations may take place.

The formula is as follows:

The European Congress is responsible for taking care of all necessary regulations with respect to the territory or other possessions belonging to the European Federal Union, related to the following Common European Interests:

1. The livability of the European Federal Union,

by regulating policies against existential threats to the safety of the European Federal Union, its States and Territories and its Citizens, be they natural, technological, economic or of another nature, or concerning the social peace.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on all natural resources and all lifeforms, on climate control, on the implementation of climate agreements, on protecting the natural environment, on ensuring the quality of the water, soil, air, and on protecting the outer space;

(b) to regulate policies on preventing and fighting pandemics

(c) to regulate the policy on the safety and availability of food and drinking water;

(d) to regulate the policy on preventing scarcity of natural resources and dysfunctional supply chains;

(e) to regulate the policy on social security, consumer protection and child care;

(f) to regulate the policy on employment and pensions;

(g) to regulate the policy on health throughout the European Federal Union, including prevention, furthering and protection of public health, professional illnesses, and labor accidents;

(h) to regulate the policy on justice and on establishing federal courts, subordinated to the European Court of Justice.

2. The financial stability of the European Federal Union,

by regulating policies to secure and safe the financial system of the Federation.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on federal tax, imposts, and excises, uniformly in all territories of the European Federal Union, on the debts of the Federation, on the expenses to fulfill the duties imposed by this and on borrowing money on the credit of the Federation;

(b) to regulate the policy on installing a fiscal union;

(c) to regulate the policy on supervising the system of financial entities;

(d) to regulate the policy on coining the federal currency, its value, the standard of weights and measures, the punishment of counterfeiting the securities and the currency of the Federation.

3. The internal and external security of the Europese Federale Unie,

by regulating policies on defence, intelligence and policing of the Federation.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on raising support on security capabilities, among which the policy on one common defence force (army, navy, air force, space force) of the Federation, on compulsory military service or community service, and on a national guard;

(b) to regulate policies in the context of external conflicts, policies on sending armed forces outside the territory of the Federation, on military bases of a foreign country on the territory of the federation, on the production of defensive weapons, on the production of weapons for mass destruction, on the import, circulation, advertising, sale, and possession of weapons, on the possibility of bearing arms by civilians;

(c) to regulate the policy on declaring war, on captures on land, water, air, or outer space, on suppressing insurrections and terrorism, on repelling invaders, and on fighting autonomous weapons;

(d) to regulate the policy on fighting cybercrimes and crimes in outer space;

(e) to regulate the policy on one federal police force;

(f) to regulate the policy on one federal intelligence service;

(g) to regulate fighting and punishing piracy, crimes against international law and human rights;

4. The economy of the Europese Federale Unie,

by regulating policies on the welfare and prosperity of the Federation.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on the internal market;

(b) to regulate the policy on transnational production sectors like industry, agriculture, livestock, forestry, horticulture, fisheries, IT, pure scientific research, inventions, industrial product standards;

(c) to regulate the policy on transnational transport: road, water (inland and sea), rail, air, and outer space; including the transnational infrastructure, postal facilities, telecommunications as well as electronic traffic between public administrations and between public administrations and Citizens, including all necessary rules to fight fraud, forgery, theft, damage and destruction of postal and electronic information and their information carriers;

(d) to regulate the policy on the commerce among the Member States of the Federation and with foreign nations;

(e) to regulate the policy on banking and bankruptcy throughout the Federation;

(f) to regulate the policy on the production and distribution of energy supply;

(g) to regulate the policy on consumer protection;

5. The science and education of the Europese Federale Unie, by regulating policies on the improving the level of wisdom and knowledge within the Federation.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on scientific centers of excellence;

(b) to regulate the policy on transnational alignment of pioneering research and related education;