Amending Article III of the constitution

Dear Members of the Group 55+ of FAEF’s Citizens’ Convention,

Building a federation is mainly a matter of structure and procedures. It is not about substantive policy. There is no such thing as federalist policy, for example, in the sense of federalist agricultural policy. There are, however, the policies of the federation. But its content is not determined by the fact that it has a federal form of organisation but by the political views and decisions of the members of the House of the Citizens and of the States and of the federal executive. The federation itself has no political colour. It is not left-wing; it is not right-wing, is neither progressive nor conservative. It is a safe house for all European citizens, regardless their political, social, religious belief. A structure with procedures that are geared as much as possible towards taking care of Common European Interests, in other words, interests that individual Member States can no longer defend on their own. And those Common European Interests are one of the few places in the federal constitution where procedures are linked to content.

That is what this Progress Report 13 is about.

This Report is intended to prepare for the improvement of Article III- Powers of the Legislative Branch. Article II will be completed during the course of this week with a final discussion on some issues that have not yet been finalized in the Discussion Forum. In the meantime, the FAEF Board is preparing the approach to Article III, which the 55+ Group will improve from 4 until 25 December.

In Progress Report 12 attention was drawn to three important issues.

- Specifying the list of Common European Interests (Article III, Section 2).

- Anti-corruption rules (Article III, Section 5).

- The matter of the State of the Union (Article V, Section 2, Clause 1).

Point 1 requires very close attention from the 55+ Group because improving Section 2 significantly strengthens the federal character of our draft constitution on the one hand and guarantees on the other hand the sovereign nature of the complex of competences of the Member States.

Point 2 is about very tough anti-corruption provisions aimed at preventing money from influencing elections. The Board assumes that point 2 requires no introduction at this time.

Item 3 can wait until we deal with Article V.

- Improving the list of Common European Interests (Article III, Section 2)

1.1 The difficult task of formulating the best possible Common European Interests

If one sees the Preamble as the soul of the Constitution, then Section 2 of Article III is its heart. A federal constitution contains to a large extent procedural law to delineate the complex of independent powers of the federation (working for the whole) from the complex of sovereign powers of the member states (working for their own state). Article III mixes procedural provisions with substantive issues and the way they are to be dealt with partly by the federation and partly by the member states.

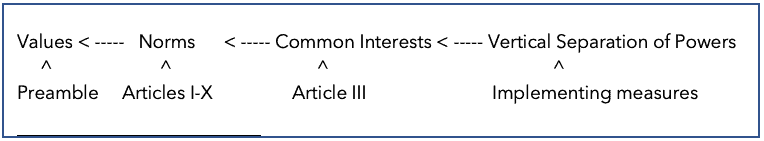

This requires a return to the passage on Values and Interests in the General Observations of the Explanation to the Preamble. The Preamble to a federal Constitution is about values. The values – explicitly formulated in the Preamble – are the objectives to be achieved through the deployment of Articles I to X. These articles contain the norms – read means – by which the values – read objectives – must be realised. The composition of a Constitution is thus a balanced relationship between values and norms or – in other words – between ends and means.

Interests on the other hand – better the Common European Interests of Europe, to be taken care of by the Federal Authority – are part of the norms and thus fall under the ten articles of the Constitution, not in the Preamble. Moreover, common interests are part of a second ends – means relationship. They are cared for and secured through a socalled vertical separation of powers/competences[1] between the federal body and those of the member states. And that is where Section 2 of Article III comes in. Note that the vertical separation of powers leads to shared sovereignty of the federal body and the Member States. Not shared competences, source of conflicts, as in the Treaty of Lisbon.

Note that both ends – means relationships are part of the ingenious system of checks and balances and require such attention that the ends are clear, that the means are clear and that the means can actually realise the ends. A simple diagram shows the relations:

1.2 The limitative and exhaustive list of Common European Interests

It is an indissoluble standard of federal statecraft that the powers of the federal body are limitative and exhaustive. The present text of Section 2 of Article III is not good enough in that respect. It merely formulates what the federal government, of both Houses of the European Congress, may do. But that does not make clear what exactly the limitative and exhaustive Common European Interests are.

Therefore, the FAEF Board presents the following – provisional – list of seven Common Interests to the Group 55+. Thereafter, in 1.3, it is about the way in which the representation of these Common European Interests – partly by the federal body, partly by the Member States themselves – could best be arranged.

The sentences with a), b) c) …. indicate provisionally subjects that should be included in the vertical division of competences: which competences do the member states entrust to the federal body and which do they keep themselves? They serve as an idea of the discussions and negotiations explained in 1.3.

1. The internal and external security of the Federation

a) a common defence force for the Federation; national guards for the Member States

b) a federal police force, but the Member States also have their own police forces

c) a federal intelligence service, but the Member States also have their own intelligence services.

2. The financial stability of the Federation

a) supervision of the entire system of financial entities (this is the subject of the in-depth study by Moses Marinho Sanches

b) introduction of a fiscal union, see Toolkit Section 3.8

c) federal taxation, while reducing the taxes of the Member States

d) accompanying Institution: the European Court of Auditors,

3. The livability of the Federation

a) climate control, implementation of climate agreements

b) social security, basic income, homeless, tramps, outcasts, stateless, immigrants

c) health, pandemic policy, transnational hospitals

d) justice

e) accompanying Institutions: The European Court of Justice, Federal Courts and the European Ombudsman.

4. The economy of the Federation

a) free movement of people, internal market

b) transnational production sectors: industry, agriculture, livestock, forestry, horticulture, fisheries, IT, pure scientific research, inventions

c) transnational transport, road, water (inland and sea), rail, air, space

d) energy supply.

5. The science and education of the Federation

a) scientific centres of excellence

b) transnational alignment of pioneering research and related education.

6. The social and cultural ties of the Federation

a) strengthening unity in diversity. Acquire the new and cherish the old

b) provide all arts and sports with a federal basis.

7. The foreign affairs of the Federation

a) policy directed at external cooperation to strengthen the other points

b) member states have their own foreign policy plus embassies for national interests.

1.3 The difficult task to formulate the best possible vertical separation of powers/competences

For the sake of good order, we will first set out the following anchor points.

Firstly. If the constitution is ratified by enough Citizens to establish the Federation

the Common European Interests will be established. See Principle 2 below. The meaning of this is: the Citizens have spoken; this list is non-negotiable during the debate necessary to determine which aspects of these seven Common European Interests should be entrusted to the care of the federal body and which aspects remain within the sovereign competence of the Member States. The future will tell when and why this list should be changed by amending the constitution.

Secondly. The vertical separation of powers is the same as establishing subsidiarity. In other words, nowhere in a well-designed federal constitution is there a sentence that points to the principle of subsidiarity for the simple reason that the concepts of ‘federal constitution’ and ‘subsidiarity’ coincide.

Thirdly. The vertical separation of powers leads to shared sovereignty of the federal body and of the Member States. The Member States retain their sovereignty in the sense that they do not transfer parts of their sovereignty to the federal body and would thus lose those sovereignty. What they are doing is entrusting some of their powers to the federal body because that body can look after Common European Interests better than the member states themselves. Thus, the Member States make their relevant powers dormant. The effect is shared sovereignty.

Fourthly. The vertical separation of powers will always be a matter of debate and will sometimes require adjustment. That is why we propose that the outcome of the discussions and negotiations on the vertical separation of powers should be an appendix to the constitution. Not a fixed part of the constitution itself, to prevent that any necessary adjustments of the vertical separation will force to amend the constitution itself.

On the basis of a few principles, the FAEF Board lays down the following procedure for determining the vertical separation of powers.

Principle 1 – from bottom to top

The biggest mistake one can make is to arrange the allocation of powers from top to bottom. Wherever possible in the construction of a federal state, one should always work from the bottom up.

This implies asking the member states which parts of their complex of competences they wish to make dormant, so that the federal body can dispose of them to take care of the seven Common European Interests.

We must be careful not to think in terms of decentralization. This does happen in federal states that are centrifugally built: a centre creates parts. For instance such as Belgium: a centre of the decentralized unitary state decentralized top-down so much that it created several sovereign regions (Wallonia and Flanders). But the effect of such a course of action is that there will always remain unitary/centralist aspects. If countries such as Spain and the United Kingdom were to decide to further decentralize their already existing devolved autonomous regions into parts of a federal state, they would run the risk of creating a relatively imperfect federal state there as well. Our constitution is based on the classic method of federalisation, a centripetal construction: bottom up, the parts together create a centre.

Principle 2 – debate and negotiation by Common European Interests

If the electorates of at least three EU – or non-EU – member states ratify the constitution by a majority, and if their parliaments follow the will of their people, the debate and negotiation on the powers that the member states entrust to the federation start. This process is as follows:

a) Internal deliberation by individual Member States

Each member state has two months to prepare a document in which it puts forward proposals on the powers it wishes to entrust to the federal body. In total, they draft seven documents, one for each Common European Interest. In doing so, they give an insight into the way in which they think the federal body should be vested with substantive powers and material resources. A protocol establishes the requirements that the documents must meet in order to be considered. The central requirement is that they must deal with the representation of European interests that a member state cannot (or can no longer) represent in an optimal manner itself.

b) Aggregation of the documents

Under the leadership of FAEF, a Committee is created beforehand to regulate the transition from the treaty-based to the federal system. Led by FAEF, that Committee consists of (a) non-political experts from the seven Common European Interests and (b) non-political citizens. Point (a) is required for expertise. Point (b) is required to prevent the deliberation and decision-making on the vertical separation of powers from degenerating – as has been the case since 1951 – into nation-state advocacy. The Committee aggregates the seven documents of each Member State into a total sum of powers to be vertically separated, and the substantive and material consequences. Two months are available for this.

c) Final decision-making

The aggregated document is the agenda for a seven-week deliberation. One week per Common European Interest. Under the leadership of the Committee, final decisions are taken on the best balanced allocation of powers from the Member States to the federal body. This final document will be an appendix of the constitution.

d) The start of the construction of the federal Europe

The result of c) marks the beginning of the building of the federal Europe.

1.4 Conclusion

The FAEF Board submits this Progress Report 13 to the Group 55+ and awaits the improvements to this proposal to be discussed in the Discussion Forum.

On behalf of the Board,

Leo Klinkers

President

[1] For a good understanding of the vertical separation of powers, see sections 2.14, 3.4, 4.2.5, 4.2.8, 4.4.1, 5.2, 5.3.2, 5.4, 6.15, of the previously mentioned Toolkit: https://www.faef.eu/wp-content/uploads/Constitutional-Toolkit.pdf.