PART 4 | 4 DECEMBER 2021 – 15 JANUARY 2022

The content of Article III explains what is meant by the vertical separation of powers between the Member States and the federal body. Because the Member States have common interests that they cannot defend on their own, they entrust some of their powers to a federal body. They do not transfer their powers but make them dormant, as it were. Their sovereignty remains unaffected. The federal body serves the common interests of the states with powers of the states. If the federal body mishandles the powers of the states, that 'dormancy' of the powers is reversed because - in accordance with Article I of the Constitution - the federation is the property of the Citizens and of the States.

Well, Article III is mainly about that exhaustive list of powers of the federal body for the promotion of common interests of the member states. Note well: the Preamble is about values, Article III is about how the federation will try to guarantee those values.

Section 1 is important from the point of view of revenue of the federation. The House of Citizens may make tax laws while the Senate may make proposals to amend them: checks and balances.

Both Houses may draft federal laws. This differs considerably from what is customary in most countries. There, governments draft laws and parliaments act as the bodies to enact or amend them. This power of the legislature to draft laws itself forces the President to accept them for implementation or not. If not, a process of arguments and counter-arguments takes place in which the number of votes within the legislature ultimately determines who wins.

Section 2 of Article III is the exhaustive list of powers of the European Congress. What the President, as head of the executive, may do with it is stated in Article V on the powers of the President. I will deal with that later.

Again: the Preamble contains the values that the federation wants to preserve, Section 2 of Article III is about the list of limitative powers of the legislature to protect those values. So that list is not about policy, for example about reducing CO2 to protect the climate. That the legislature can make policy on that point is stated in Section 2 under g: "to regulate and enforce the rules to further and protect the climate and the quality of the water, soil and air;". But it is up to the members of the European Congress to decide what the content of that policy will be. The constitution is not left-wing, not right-wing, not progressive, not conservative. It provides the basis for setting a political course with policy measures. But what those policies will be is determined by the members of the House of Citizens and the Senate.

Members of the 55+ group who wish to table amendments for Section 2 are asked to use this level of abstraction. An amendment along the lines of: "The USE is reducing CO2 emissions by 50% by the year XX" is not useful. That is policy and has no place in a constitution.

Once again. The constitution has no political colour. It is the 'common house' in which we all have to live, looking for happiness, prosperity, and freedom, as much as possible. If we build a constitution based on specific policies, we will easily attract people, organisations and parties that are in favour of those specific policies, but we will lose the support of all other persons, organizations, parties. A federal constitution must not be a Socialist constitution, it must not be a Christian Democrat constitution, it cannot be left, or right, or whatever. It is a constitution for all European citizens and for all European countries and regions. And that must be expressed in words of constitutional law. Not in words of politics and policies.

In Section 3, the first Clause states that immigration policy of individual states will be phased out and become a federal matter after XX years. The implicit reservation that member states may first pursue their own immigration policies for some time dates back to the time when a treaty-based common EU policy not yet existed. Therefore, this is a good Clause to amend in the sense that immigration policy is a matter for federal authority from the outset.

Sections 4 and 5 contain provisions limiting powers. In Section 5, Clauses 4 to 9 contain strict provisions to prevent political corruption. Influencing elections and policy with money must be out of the question.

Article III – Powers of the Legislative Branch

Section 1 - Way of proceeding to make laws

- The House of the Citizens has the power to initiate tax laws for the United States of Europe. The Senate has the power - as is the case with other law initiatives by the House of the Citizens - to propose amendments in order to adjust federal tax laws.

- Both Houses have the power to initiate laws. Each draft law of a House will be presented to the President of the United States of Europe. If he/she approves the draft he/she will sign it and forward it to the other House. If the President does not approve the draft he/she will return it, with his/her objections, to the House initiating the draft. That House records the presidential objections and proceeds to reconsider the draft. If, following such reconsideration, two thirds of that House agree to pass the bill it will be sent, together with the presidential objections, to the other House. If that House approves the bill with a two third majority, it becomes law. If a bill is not returned by the President within ten working days after having been presented to him/her, it will become law as if he/she had signed it, unless Congress by adjournment of its activities prevents its return within ten days. In that case it will not become a law.

- Any order, resolution or vote, other than a draft law, requiring the consent of both Houses – except for decisions with respect to adjournment – are presented to the President and need his/her approval before they will gain legal effect. If the President disapproves, this matter will nevertheless have legal effect if two thirds of both Houses approve.

Section 2 – Substantive powers of the Houses of the European Congress

The European Congress has the power:

- to impose and collect taxes, imposts and excises to pay the debts of the United States of Europe and to provide in the expenses needed to fulfill the guarantee as described in the Preamble, whereby all taxes, imposts and excises are uniform throughout the entire United States of Europe;

- to borrow money on the credit of the United States of Europe;

- to regulate commerce among the States of the United States of Europe and with foreign nations;

- to regulate throughout the United States of Europe uniform migration and integration rules, what rules will be co-maintained by the States;

- to regulate uniform rules on bankruptcy throughout the United States of Europe;

- to coin the federal currency, regulate its value, and fix the standard of weights and measures; to provide in the punishment of counterfeiting the securities and the currency of the United States of Europe;

- to regulate and enforce the rules to further and protect the climate and the quality of the water, soil and air;

- to regulate the production and distribution of energy;

- to make rules for the prevention, furthering and protection of public health, including professional illnesses and labor accidents;

- to regulate any mode of traffic and transportation between the States of the Federation, including the transnational infrastructure, postal facilities, telecommunications as well as electronic traffic between public administrations and between public administrations and Citizens, including all necessary rules to fight fraud, forgery, theft, damage and destruction of postal and electronic information and their information carriers;

- to further progress of scientific findings, economic innovations, arts and sports by safeguarding for authors, inventors and designers the exclusive rights of their creations;

- to establish federal courts, subordinated to the Supreme Court;

- to fight and punish piracy, crimes against international law and human rights;

- to declare war and make rules concerning captures on land, water or air; to raise and support a European defense (army, navy, air force); to provide for a militia to execute the laws of the Federation, to suppress insurrections and to repel invaders;

- to make all laws necessary and proper for carrying out the execution of the foregoing powers and of all other powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States of Europe or in any Ministry or Public Officer thereof.

Section 3 – Guaranteed rights of individuals

- The immigration of people, by States considered to be permissible, is not prohibited by the European Congress before the year 20XX.

- The right of habeas corpus is not suspended unless deemed necessary for public safety in cases of revolt or an invasion.

- The European Congress is not allowed to pass a retroactive law nor a law on civil death. Nor pass a law impairing contractual obligations or judicial verdicts of whatever court.

Section 4 – Constraints for the United States of Europe and its States

- No taxes, imposts or excises will be levied on transnational services and goods between the States of the United States of Europe.

- No preference will be given through any regulation to commerce or to tax in the seaports and air ports of the States of the United States of Europe; nor will vessels or aircrafts bound to, or from one State, be obliged to enter, clear or pay duties in another State.

- No State is allowed to pass a retroactive law nor a law on civil death. Nor pass a law impairing contractual obligations or judicial verdicts of whatever court.

- No State will emit its own currency.

- No State will, without the consent of the European Congress, impose any tax, impost or excise on the import or export of services and goods, except for what may be necessary for executing inspections of import and export. The net yield of all taxes, imposts or excises, imposed by any State on import and export, will be for the use of the Treasury of the United States of Europe; all related regulations will be subject to the revision and control by the European Congress.

- No State will, without the consent of the European Congress, have an army, navy or air force, enter into any agreement or covenant with another State of the Federation or with a foreign State, or engage in a war, unless it is actually invaded or facing an imminent threat which precludes delay.

Section 5 – Constraints for the United States of Europe[1]

- No money shall be drawn from the Treasury but for the use as determined by federal law; a statement on the finances of the United States of Europe will be published yearly.

- No title of nobility will be granted by the United States of Europe. No person who under the United States of Europe holds a public or a trust office accepts without the consent of the European Congress any present, emolument, office or title of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince or foreign State.

- No personnel, whether paid or unpaid, of the government, government contractors or entities receiving direct or indirect funding from the government shall set foot on foreign soil for the purpose of hostilities or actions in preparation for hostilities, except as permitted by a declaration of war by Congress.

- No person or entity, whether living, robotic or digital, may contribute more than one day's wages of the average U.S. laborer to a person seeking elected office in a particular election cycle, in currency, goods, services or labor, whether paid or unpaid. Anyone seeking an elected position that accepts more than this amount in any form, and anyone who seeks to circumvent this statutory limit on campaign contributions, will be barred from holding office for life and will serve a minimum term of imprisonment of five years.

- No person or entity that has directly or indirectly received funds, favors or contracts from the government during the last five years may contribute to an election campaign under the sanctions described in paragraph 6. In addition, any entity seeking to circumvent this limitation shall be fined five years of its annual turnover, payable on conviction.

- Any contribution, whether direct or indirect, in cash, goods, services or labour, whether paid or unpaid, made to a person seeking elected office must be made public within forty-eight hours of receipt. The contribution from each entity must bear the name of the person or persons responsible for managing the entity. An entity seeking to circumvent this limitation shall be fined five years on an annual basis, payable on conviction.

- No individual shall spend more than one month of the average monthly wage of the average worker on his own campaign for an elected office. Anyone wishing to circumvent this statutory limit on campaign contributions will be barred from holding office for life and will serve a minimum sentence of five years imprisonment.

- No government employee may accept a position in a private entity that has accepted government funding, favors or contracts for a period of ten years after leaving the government office during the last five years.

- Every institution and agency of government, and every entity or person that has directly or indirectly received government funding, favors or contracts, will be subject to an independent audit every four years, and the results of these forensic audits will be made public on the date of their issue. Any entity attempting to circumvent or avoid this requirement will be fined five years in revenue, payable in the event of a conviction. Any person seeking to circumvent or avoid this requirement must serve a minimum term of imprisonment of five years.

[1] Clauses 3-9 of Article III were added by Leo Klinkers, taken from Charles Hugh Smith, 10 Common- Sense Amendments to the US Constitution, 21 February 2019.

The powers of the Congress concern matter of national importance. For example, currency, federal taxation, commercial relations with other countries, foreign affairs and defence. And a number of other - exhaustively enumerated - matters.

So, each bill comes from one of the Houses and is first submitted to the President. He can either sign it or give a reasoned veto. In the latter case, it goes back to the House concerned for reconsideration. If that House and the other House then adopt the proposal by a two-thirds majority, the law passes.

Explanation of Section 1

Here we choose a different structure from that of the American Constitution. The American Article I of that Constitution has ten Sections. These deal with both the organisation of Congress and its powers. We think it is better to split these two subjects. Therefore, we have given our Article II the title of ‘Organisation of the Legislature’ which then covers Sections 1-6. We then deal with Sections 7-10 in a new Article III under the title of 'Powers of the Legislature'. The Sections 7-10 of the American Article I are then numbered Sections 1-4 in our Article III.

So, both Houses make initiative laws. Not the President and the Ministers of his Cabinet. They do not even act in the Houses. This strict separation of legislative and executive power guarantees the autonomy of the European Congress in its core task: the drafting and final approval of federal laws.

Section 1 gives the exclusive power to the House of the Citizens to make tax laws. Unlike legislation in the general sense, the Senate therefore does not have that power. However, the Senate may try to change those tax laws through amendments. The reason for declaring only the House of the Citizens competent to take an initiative in this regard is based on the consideration that 'groping in the purse of the citizens' is solely and exclusively at the discretion of the representatives of those citizens.

The House of the Citizens thus decides what type of federal taxation will take place: income tax, corporation tax, property tax, road tax, wealth tax, profits tax and/or value added tax. Or perhaps it will leave those types of tax to the jurisdiction of the States and creates only one new type of tax under the name Federal Tax, provided that States' taxes are simultaneously reduced or abolished to prevent this Federal Tax from being imposed at the expense of the Citizens. We say no more about this because it is a subject for the politically elected. That is why we do not comment here on the dispute regarding the harmonization of taxes, for example corporate taxation.

In Clause 2, the application of the Lex Silencio Positivo, a rule of Roman law, is remarkable: if the President does not express his opinion within ten days, the proposal automatically becomes law. If the President rejects the bill, he must give reasons for his rejection and return it to the House that drafted it. This is called the President's veto. The word 'veto', by the way, is not explicitly mentioned in the US Constitution. Nor is it in our article.

At this point, it seems useful to briefly discuss one of the consequences of the American choice to support the principle of the trias politica with an ingenious system of checks and balances. In practice, this sometimes leads to a situation in the US where one of the Houses, together with the President, forms a blockade to solve a budget crisis (fiscal cliff). On a superficial view, one could attribute this to a constitutional system error: if both powers stand on their constitutional lines, an impasse arises. And that could be seen as an error of the American Constitution. But this view is wrong if one goes back to the main reason for establishing this system of checks and balances: never again should anyone be the absolute boss over everyone else. This forces all parties involved, in case of a possible deadlock, to show the responsibility that the Citizens have given to them. And that is no more or less than ensuring that the deadlock is resolved. The continuation of such a sad situation is thus not due to a systemic error of the US Constitution, but to the inability of the politicians involved to take responsibility for the common good.

So, in the US Presidential System, none of the three branches - the legislature, the executive and the judiciary - is the boss of the other. There is only one boss: the people. The people can demonstrate that power in two ways: in elections and in a referendum that offers a decisive solution when the three branches of government have reached an impasse. The referendum matter is discussed in 6.8.

Explanation of Section 2

The limitative enumeration of the powers of the federal authority is a typical feature of the federal system: the States may regulate anything that is not explicitly assigned to the federal authority. It is precisely laid down that the federal government may not interfere in matters that are part of the States' complex of powers. See here the protection of the sovereignty of the States. And vice versa, it is also laid down in what respect those States may not interfere with federal authority except with the authorisation of Congress.

Here is exactly one of the main differences between intergovernmentalism and a federation: no hierarchy at the top, shared sovereign legislative power of the Federation and its constituent parts, the States. So, no interference in the federal level of government and in that of the States. This contradicts the popular misconception that a federal State is a superstate that breaks down and absorbs the sovereignty of the constituent states. Quod non. In a federal system, the powers of the States and the Federal body remain separate.

The limitative enumeration of the powers of the legislature is intended to regulate common interests that Citizens or States cannot provide for. The essence of the vertical distribution of power is that Citizens and States ask a federal body to take good care of a limited set of common interests (for which they are also willing to pay), without this federal body having the right to assume that it is then everyone's boss. All other powers remain with the Citizens and the States, untouchable by the federal authority. The States retain their own Parliament, Government and Judicial Power for what is not assigned to the United States of Europe.

This Section 2 is our version of the so-called 'Kompetenz Katalog' which Germany proposed during the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, and many times afterwards, but which was always rejected by other EU countries. This is one of the serious shortcomings of the intergovernmental system.

Our list is completely different from the exhaustive lists (plural) that we find in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union with regard to the European Union. Not only are they not precisely and genuinely exhaustive, but they are also thwarted by the uncontrollable principle of subsidiarity, the hierarchical exercise of powers and the sharing of competences: all of these are a curse in a truly federal temple because they encroach on the sovereignty of the States. For the record, this principle of the limitative enumeration of federal powers is one of the greatest achievements of the debates in the Philadelphia Convention and was achieved within two weeks.

This seems a good place to quote Frank Ankersmit, emeritus professor of the History of Philosophy. In the Dutch Yearbook of Parliamentary History 2012, entitled 'The United States of Europe', he writes among other things:

"There is no point in going into decision-making in Europe in this place, and so it is sufficient to note that it is at odds with everything that has been thought up in the history of political philosophy about public decision-making. This decision-making in Europe is completely unique in history - and that is certainly not meant in a positive sense. Given the immense problems of European unification, one can understand that; but it is and remains an ugly thing. More specifically, this decision-making process is in fact the official codification of all the uncertainties concerning the ultimate goal of European unification. It is as if the European administrators deliberately translated this uncertainty into a governance structure that is the organisational expression of it. It is as if they wished to indissolubly enshrine Europe's inability to jump over its own shadow sooner or later in an administrative structure that would actually make this impossible.”

Compare this with the already mentioned systemic errors (see Chapter 3) of the Lisbon Treaty. It is such a flawed document (legislative, democratic, organisational, decision-making) that renewal is only possible by stepping out of it: 'step out of that box' and avoid the pitfall of trying to improve the system by adapting that flawed Treaty. After all, it is filled with systemic errors. Every new amendment will be poisoned by these errors because they are, as it were, 'genetically' burned in.

Those in positions of leadership in the intergovernmental system do not realise how destructive wrong legislation is to a society. Fundamental knowledge and understanding of the need for well thought-out constitutional design as a basis for a well-functioning society is apparently absent. Insufficient knowledge and courage to make a substantial contribution to the creation of the United States of Europe.

To accept the Treaty of Lisbon as the basis for the pursuit of a united Europe is, in our view, a form of undesirable relativization of law. As a trivialization of the need to ensure in all circumstances that the constitutional basis of society has a professionally formulated codification. Even though parts of the law, especially administrative law, have acquired an instrumental function (law as an instrument to achieve political policy goals), there are and will remain doctrines of inalienable, fundamental law which neither politics nor policy may tamper with. The 'rule of law' means that no one is above the law. But that only has meaning if the making of that law is done according to irrefutable standards, not polluted by political folklore.

Now on to our draft Federal Constitution. Essential additions compared to the US Constitution are:

- Clause d, immigration policy as a federal matter and no longer belonging to a European member state, but with the cooperation of the States in the enforcement of the federal rules, e.g., through their services of assistance, education, and police.

- Clause j, the basis for a federal approach to a European digital (electronic) agenda plus the fight against cybercrime.

- Clause n provides for the creation of federal armed forces, i.e., one European army of land forces, naval forces, and air forces. A well-known national(istic) driven point of contention, but as provincial folklore under a federal Constitution not worth contesting.

So, this Section 2 is about the most important aspect of a Federation: the vertical separation of powers between the Federation on the one hand and the Citizens and States on the other. What the European Congress may regulate is listed there exhaustively. However, this does not mean that it is immediately clear how many Ministers the executive should or could consist of. So, for which policy areas should there be a Minister with his or her own Ministry from the outset of the United States of Europe? We will deal with this under the organisation of the Executive.

As for this exhaustive list, three distinctions should be made.

Firstly, we note that the United States of Europe is logically also competent to exercise the powers assigned to it not only within the Federation but also outside, for example by concluding treaties. We link the powers of the Federation both to its internal policy and its foreign policy. The same applies to the States that are members of the Federation. How this works is covered in the organisation of the Executive.

Secondly, we must point out the last power of Section 2, Clause o. In the text of the US Constitution "To make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof." This is the famous 'Necessary and Proper Clause': Congress can make all the laws it thinks it needs. But if they do not unmistakably arise from the limitative set of powers under their Article I, Section 8 (our Article III, Section 2) the President can veto them. Or the Supreme Court can declare them unconstitutional, the so-called 'Judicial Review'. See Chapter 10.

Thirdly, another important aspect. The US Congress actually has even more powers than those mentioned in its Constitution under Article I, Section 8 (our Article III, Section 2). We are now entering the realm of the so-called 'Implied Powers' (see further Chapter 10): powers that are not literally stated in the Constitution, but that are derived from the complex of powers of the American Section 8.

One of the most important is called 'Congressional Oversight'. This oversight - organised mainly through parliamentary committees (both standing and special), but also with other instruments - concerns the overall functioning of the Executive branch and Federal Agencies. The aim is to increase effectiveness and efficiency, to keep the executive in line with its immediate task (execution of laws), to detect waste, bureaucracy, fraud and corruption, protection of civil rights and freedoms, and so on. It is a comprehensive monitoring of the entire policy implementation. This, by the way, is not something of the recent past, it arose from the inception of the Constitution and is an undisputed part of the ingenious system of checks and balances.

Mind you, the Constitution does not know this 'Congressional Oversight' in so many words, but it is supposed to be an inalienable extension of the legislative power: if you are authorised to make laws, you must also be authorised to control what happens in their implementation. It is self-evident in an administrative cycle.

Of course, there have been attempts to demonstrate with a strict interpretation of the US Constitution that this form of 'Implied Powers' is not in accordance with the Constitution. However, the US Supreme Court has always rejected this claim. This is in line with the vision of President Woodrow Wilson, who saw this parliamentary oversight as being just as important as making laws: "Quite as important as legislation is vigilant oversight of administration." All this in the knowledge that the US Constitution, in Article I, Section 9, determines the limits within which the US Congress may exercise the limitative powers of their Section 8.

We would like to draw attention to some specific Clauses of our amended Section 2.

Firstly, Clause a, the power to levy taxes and the like. This is necessary in America to pay the debts and 'for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States'. We have replaced the words in inverted commas with “necessary for the fulfilment of the guarantee set forth in the Preamble”. In our view, the generation of the federal authority's own income should extend beyond the payment of the Federation's debts and the funding of defence and general welfare expenditures. In addition to the explicit reference to being able to pay one's debts, we believe it is important that a clear link is made here with the guarantee in the Preamble. In other words, that such taxation is also there to pay for the expenses "of liberty, order, safety, happiness, justice, defence against enemies of the Federation, protection of the environment, as well as acceptance and tolerance of the diversity of cultures, beliefs, ways of life and languages of all those who live and shall live in the territory under the jurisdiction of the Federation".

Clause c is called the 'Commerce Clause' in the US Constitution. For the United States of Europe, the application of this provision - partly in the light of the conclusion of trade treaties - will be essential for the financial-economic position of Europe. In this respect, matters such as a Fiscal Union and the internationalization of the euro (see Section 3) play an important supporting role.

Explanation of Section 3

Section 3 is devoted to principled limits on the federal powers granted to Congress in Section 2 to protect individuals. This concise Section 3 on individual rights is sufficient in this draft Constitution. No more is needed. Indeed, Section I, Clause 3 of the draft states that the United States of Europe subscribes to the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (except for the inoperative principle of subsidiarity[1]) and accedes to the Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, concluded within the framework of the Council of Europe.

The first Clause of Section 3 gives the States the right to pursue their own policy on foreigners for a few more years. From the as yet unnamed year 20XX onwards, this will be federal immigration policy. And with that, the Federation of Europe will present itself as a Federation that welcomes foreigners under certain conditions, instead of using bureaucratic and hostile policing mechanisms and legal constructions aimed at defence to keep citizens from other continents out of the Federation, or to expel them. The United States of Europe can still use tens of millions of active, enterprising peoples to enrich its cultural diversity, strengthen its economy and cope with its shrinking population. This requires a policy[2] that organises immigration for the benefit of the Federation and the immigrant. European policymakers can take inspiration from the policies of Federations such as Australia, Canada, and the United States.

Explanation of Section 4

According to Clauses 1 and 2 of this Section, neither the States of the Federation, nor the Federation itself, may introduce or maintain regulations which restrict or interfere with the economic unity of the Federation. Again, powers not expressly assigned to Congress by the Constitution in Article III, Section 2 rest with the Citizens and the States. This is the other side of the coin called 'vertical separation of powers'. Nevertheless, in America it was considered useful and necessary at the time not only to place limits on Congress in their Article I, Section 9, but also to remind the States that their powers are not unlimited. To this end, their Article I, Section 10 (our Article III, Section 4) stipulates what the States may not do.

Clause 3 imposes the same limitation on the legislative power of the States as that of the Federation, contained in Section 3(3), in order to maintain legal certainty, not to affect the exercise of judicial power and to safeguard rights of Citizens in force or enforced. It is also important, a subject that has often been addressed by the US Supreme Court, that States may not legislate to override contractual obligations. Legal certainty for contractors and litigants is of a higher order than the power to declare a contract or a court decision ineffective by law.

In Clause 4, the provision that none of the member States of the Federation may create its own currency (taken from James Madison's Federalist Paper No 44) is a clear warning to some EU Member States considering returning to their own former national currencies. Nevertheless, states are allowed to issue bonds and other debt instruments to finance their deficit spending. In other words, we are proposing to create a financial system similar to that of the USA.

Clause 5 states that export and import duties are not within the competence of the States unless they are authorised to do so. They may, however, charge for the expenses they incur in connection with the control of imports and exports. The net proceeds of permitted levies must fall into the coffers of the Federation. This matter is likely to have a high place on the agenda of the previously recommended six Senators (without voting rights) delegated by the ACP countries to the European Senate.

Clause 6 emphasizes once again that defence is a federal task. On the understanding that the European Congress may decide that a member state shall accommodate on its territory a part of that federal army and keep it ready to act in case of emergency.

Explanation of Section 5

In this Section 5 we have included a number of additional rules to combat political corruption[3]. Because gigantic sums of money are spent on election campaigns in America, there is a saying: "Money is the oxygen of American politics". In our federal constitution for the United States of Europe, Article III, Section 5 contains Clauses justifying the adage: 'Money should not be the oxygen of European politics'.

This is our description of Articles I-III of the United States of Europe. We have stuck as closely as possible to the text of the US Constitution. It is therefore conceivable that words or phrases - vital for a federal Europe - may be mistakenly missing or incorrectly worded. Or that we are regulating things here that are not necessary in the envisaged European federal context. That is why this - like the rest of our draft Constitution - is open to addition and improvement by the Citizens' Convention.

The following Articles IV-X are partly taken from the original US Constitution itself, partly supplemented and improved by texts from the amendments subsequently added to it by Congress. Here too we allow ourselves to improve the readability of the structure of the American Constitution by separating the organisation of the executive branch from the duration and vacancy of the (vice-)presidency.

[1] The principle of subsidiarity is also not mentioned in the Preamble because subsidiarity coincides with federal statehood. This has already been explained.

[2] That policy will say goodbye to Frontex, the European Border and Coastguard Agency. The way in which the European Union has allowed that agency to evolve, in terms of its powers, personnel, procedures and weapons, into a defence mechanism with no democratic control and no scrutiny by human rights organisations, thus becoming the playground of industrial lobbyists, may well evolve in the greatest anti-humanitarian crime of the 21st century.

[3] Clauses 3-9 of Article III were added by Leo Klinkers, taken from Charles Hugh Smith, ‘10 Common- Sense Amendments to the US Constitution’, 21 February 2019.

Article III – Powers of the Legislative Branch

Section 1 - Legislative procedure

- Both Houses have the power to initiate laws. They may appoint bicameral commissions with the task to prepare joint proposal of laws or to solve conflicts between both Houses.

- The laws of both Houses must adhere to principles of inclusiveness, deliberative decision-making, and representativeness in the sense of respecting and protecting minority positions within majority decisions, with resolute wisdom to avoid oligarchic decision-making processes.

- The House of the Citizens has the power to initiate legislation affecting the federal budget of the European Federal Union. The House of the States has the power - as is the case with other legislative proposals by the House of the Citizens - to propose amendments in order to adjust legislation affecting the federal budget.

- Each draft law is sent to the other House. If the other House approves the draft, it becomes law. In the event that the other House does not approve the draft law, a bicameral commission is formed - or an already existing bicameral commission is appointed - to mediate a solution. If this conciliation produces an agreement or a proposal of law, this is subject to a majority vote of both Houses.

- Any order or resolution, other than a draft law, requiring the consent of both Houses – except for decisions with respect to adjournment – are presented to the President and need his/her approval before they will gain legal effect. If the President disapproves, this matter will nevertheless have legal effect if two thirds of both Houses approve.

Section 2 - The Common European Interests

- The European Congress is responsible for taking care of the following Common European Interests:

- (a) The livability of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies against existential threats to the safety of the European Federal Union, its States and Territories and its Citizens, be they natural, technological, economic or of another nature or concerning the societal peace.

(b) The financial stability of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies to secure and safe the financial system of the Federation.

(c) The internal and external security of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on defence, intelligence and policing of the Federation.

(d) The economy of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on the welfare and prosperity of the Federation.

(e) The science and education of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on the level of wisdom and knowledge of the Federation.

(f) The social and cultural ties of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on preserving established social and cultural foundations of Europe.

(g) The immigration in, including refugees, and the emigration out of the European Federal Union, by regulating immigration policies on access, safety, housing, work and social security, and emigration policies on leaving the Federation.

(h) The foreign affairs of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on promoting the values and norms of the European Federal Union outside the Federation itself. - The Federation and the Member States have shared sovereignty concerning those Common European Interests. The European Congress derives its powers in relation to these Common European Interests from powers that the Member States of the Federation entrust to the federal body through a vertical separation of powers. This implies that new circumstances may lead to a decision by the European Congress to increase or decrease the list of European Common Interests.

- Appendix III A, being integral part of this Constitution but not subject to the constitutional amendment procedure, regulates the way the Member States decide which powers to entrust to the federal body. It also regulates the influence of the Citizens on that process.

Section 3 – Constraints for the European Federal Union and its States

- No State will introduce state-level policies or actions that can threaten the safety of its own Citizens, or of Citizens of other Member States.

- No taxes, imposts or excises will be levied on transnational services and goods between the States of the European Federal Union.

- No preference will be given through any regulation to commerce or to tax in the seaports, air ports or spaceports of the States of the European Federal Union; nor will vessels or aircrafts bound to, or from one State, be obliged to enter, clear, or pay duties in another State.

- No State is allowed to pass a retroactive law or restore capital punishment. Nor pass a law impairing contractual obligations or judicial verdicts of whatever court.

- No State will emit its own currency.

- No State will, without the consent of the European Congress, impose any tax, impost or excise on the import or export of services and goods, except for what may be necessary for executing inspections of import and export. The net yield of all taxes, imposts, or excises, imposed by any State on import and export, will be for the use of the Treasury of the European Federal Union; all related regulations will be subject to the revision and control by the European Congress.

- No State will have military capabilities under its control, enter any security(-related) agreement or covenant with another State of the Federation or with a foreign State, and can only employ military capabilities out of self-defense against external violence when an imminent threat requires this, and only for the duration that the Federation cannot fulfil this obligation. The military capabilities that are used in the above-mentioned situation are capabilities that are stationed on the State’s territory as part of that federal army.

Section 4 – Constraints for the European Federal Union

- No money shall be drawn from the Treasury but for the use as determined by federal law; a statement on the finances of the European Federal Union will be published yearly.

- No title of nobility will be granted by the European Federal Union. No person who under the European Federal Union holds a public or a trust office accepts without the consent of the European Congress any present, emolument, office, or title of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince or foreign State.

- No personnel, whether paid or unpaid, of the government, government contractors or entities receiving direct or indirect funding from the government shall set foot on foreign soil for the purpose of hostilities or actions in preparation for hostilities, except as permitted by a declaration of war by Congress.

- No person or entity, whether living, robotic or digital, may contribute more than one day's wages of the average laborer to a person seeking elected office in a particular election cycle, in currency, goods, services or labor, whether paid or unpaid. Anyone seeking an elected position that accepts more than this amount in any form, and anyone who seeks to circumvent this statutory limit on campaign contributions, will be barred from holding office for life and will serve a minimum term of imprisonment of five years.

- No person or entity that has directly or indirectly received funds, favors, or contracts from the government during the last five years may contribute to an election campaign under the sanctions described in clause 6. In addition, any entity seeking to circumvent this limitation shall be fined five years of its annual turnover, payable on conviction.

- Any contribution, whether direct or indirect, in cash, goods, services or labour, whether paid or unpaid, made to a person seeking elected office must be made public within forty-eight hours of receipt. The contribution from each entity must bear the name of the person or persons responsible for managing the entity. An entity seeking to circumvent this limitation shall be fined five years on an annual basis, payable on conviction.

- No individual shall spend more than one month of the average monthly wage of the average worker on his own campaign for an elected office. Anyone wishing to circumvent this statutory limit on campaign contributions will be barred from holding office for life and will serve a minimum sentence of five years imprisonment.

- No government employee may accept a position in a private entity that has accepted government funding, favors or contracts for a period of ten years after leaving the government office during the last five years.

- Every institution and agency of government, and every entity or person that has directly or indirectly received government funding, favors or contracts, will be subject to an independent audit every four years, and the results of these forensic audits will be made public on the date of their issue. Any entity attempting to circumvent or avoid this requirement will be fined five years in revenue, payable in the event of a conviction. Any person seeking to circumvent or avoid this requirement must serve a minimum term of imprisonment of five years.

Explanation of Section 1

Clause 1 entitles both Houses of the European Congress to make initiative laws. Not the President and the Ministers of his Cabinet. These executives do not even act in the Houses. This strict separation of legislative and executive power guarantees the autonomy of the European Congress in its core task: the drafting and final approval of federal laws.

Clause 2 is a rather revolutionary text. Laws - with commandments and prohibitions - are the strongest instrument by which a government determines the behavioural alternatives of its Citizens. Citizens who believe that laws do not sufficiently consider the requirement of inclusiveness, deliberative decision-making, and representativeness in the sense of respecting and protecting minority positions within majority decisions, with resolute wisdom avoiding oligarchic decision-making processes can challenge this up to the highest court. The Federal Court of Justice has the power to test laws against the Constitution. In this Clause 2, therefore, lies a fundamental aspect of direct democracy: citizens have the right to challenge the correctness of a law before the highest court.

Clause 3 gives the exclusive power to the House of the Citizens to make tax laws. Unlike legislation in the general sense, the House of the States therefore does not have that power. However, that House may try to change those tax laws through amendments. The reason for declaring only the House of the Citizens competent to take an initiative in this regard is based on the consideration that 'groping in the purse of the citizens' is solely and exclusively at the discretion of the delegates of those Citizens.

The House of the Citizens thus decides what type of federal taxation will take place: income tax, corporation tax, property tax, road tax, wealth tax, profits tax and/or value added tax. Or perhaps it will leave those types of tax to the jurisdiction of the States and creates only one new type of tax under the name Federal Tax, provided that States' taxes are simultaneously reduced or abolished to prevent this Federal Tax from being imposed at the expense of the Citizens. The Constitution says no more about this because it is a subject for the politically elected.

Clause 4 excludes the President's involvement in the legislative process of both Houses. The US Constitution gives the President the power to veto a draft law, but then a complicated process follows between the President and both Houses to agree or disagree. We do not consider it desirable for the President, as leader of the Executive Branch, to participate in law making, nor in interfering in a possible dispute between the two Houses. We provide the establishment of a mediating bicameral commission in case both Houses cannot work it out together.

Clause 5 gives the President a say in legislative matters of a lower level than a law.

Explanation of Section 2

If one sees the Preamble as the soul of the Constitution, then Section 2 of Article III is its heart. It mixes procedural provisions with substantive issues and the way they are to be dealt with partly by the Federation and partly by the Member States.

The end-means relationships of the Constitution

Building a federation is mainly a matter of structure and procedures. It is not about substantive policy. There is no such thing as federalist policy, for example, in the sense of federalist agricultural policy. There are, however, the policies of the federation. But their content is not determined by the fact that it has a federal form of organisation but by the political views and decisions of the members of the House of the Citizens, of the States and of the Federal Executive. The Federation itself has no political colour. It is not left-wing; it is not right-wing, is neither progressive nor conservative. It is a safe house for all European Citizens, regardless their political, social, religious belief. A structure with procedures and guarantees that are geared as much as possible towards taking care of Common European Interests. In other words, interests that individual Member States can no longer take care of on their own.

Section 2 shows the list Common European Interests in relation to substantive subjects for which the Federal Authority needs powers to look after those interests. Because this federation is built on the principles of centripetal federalizing (by building from the bottom up the parts create the whole) the Member States shall determine for which Common European Interests they are entrusting which powers to the federation. This is the most important condition for preventing the federation from developing into a superstate. Federations that are built top down (centrifugal federalisation: a central government creates parts) have the characteristic that there will always be centralist aspects in the federation, with the risk of weakening the classical federal structure that aims to ensure that the parts always remain autonomous, independent, and sovereign.

Thus, the powers of the federal body come from the Member States, not in the sense of transferring or conferring, but in the sense of entrusting: the Member States make some of their powers dormant, as it were, so that the Federation can work with them to realise the Common European Interests. That is the socalled vertical separation of powers between the Member States and the Federal Authority, leading to shared sovereignty between the two.[1]

[1] The vertical separation of powers is the same as establishing subsidiarity. In other words, nowhere in a well-designed federal constitution is there a sentence that points to the principle of subsidiarity for the simple reason that the concepts of ‘vertical separation of powers’ and ‘subsidiarity’ coincide. See for more information the paragraphs 4.2.5, 4.2.8, 5.2, 5.3.2, 5.4 of the aforementioned Toolkit: https://www.faef.eu/wp-content/uploads/Constitutional-Toolkit.pdf.

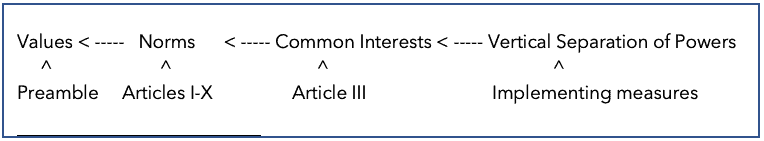

This requires a return to the passage on ‘Values and Interests’ in the General Observations of the Explanation to the Preamble. The Preamble to a federal Constitution is about values. The values are the objectives to be achieved through the deployment of Articles I to X. These articles contain the norms – read means – by which the values – read objectives – must be realised. The composition of a Constitution is thus a balanced relationship between values and norms or – in other words – between ends and means.

Interests on the other hand – better the Common European Interests of Europe, to be taken care of by the Federal Authority – are part of a second ends–means relationship. They are the means to realize the norms. And they are cared for and secured through the Vertical Separation of Powers between the Federal body and the Member States. So, that is a third means to end relationship.

Note that these three ends–means relationships are part of the ingenious system of checks and balances and require such attention that the ends are clear, that the means are clear and that the means can realise the ends. The arrows in the diagram – from right to left - show the means to end relations:

The FAEF Citizens’ Convention started the process of improving a provisional Constitution text with the perception that there are Values and Common European Interests; and that we can achieve (much) more through cooperation. Realization of these Common Interests are the objectives of forms of cooperation between the Member States and a Federal Authority. By expanding the scope, scale, and depth of the collaboration, it becomes possible to define those Common Interests in terms of means to fulfill the Norms and the Norms to fulfill the Values. These Values are understood as the foundation of the Federation, and as the ultimate objectives to be achieved. They have become the objectives in terms of the ‘what’ and indicate the desired direction (of development) for the Federation.

The Articles I - X concern principles for the organization of the Federation (structure and process) - the ‘how’ - and reflect (must be consistent with) the Values. The Articles can be considered Norms. i.e. rules and expectations (of ‘behavior’) that can be enforced. They are the means to fulfill the Values.

The Common Interests are the ‘where’. They can be considered ‘result areas’ that are established with a centripetal approach to federalization (bottom-up, minimalistic/cautious approach). These result areas are the more concrete issues/challenges where the Federation can provide added value for the Member States and the Citizens of the federation. The ‘field of activity’ of the Federal Authority is defined through the Common European Interests, that are identified by the Member States and its Citizens.

The Vertical Separation of Powers defines the content, the depth and the scope of the Common European Interests and is the beginning of the series of goal-means relationships. Anything that goes well - or perhaps not well - in the process of the vertical separation of powers by which Member States entrust powers to the Federal body will positively or negatively affect the meaning and value of the Common Interests. That, in turn, will affect the quality of the Norms and, in turn, that will affect the quality of achieving the Values. Thus, the success of the vertical separation in a good cooperative effort ultimately determines the success of what the Federation aims to achieve with the Values of the Preamble.

The Clauses of Section 2

Clause 1 lists the Common European Interests. This is the fulcrum of a federal Constitution. The only reason to make a centripetal federation is that States realise that they can no longer look after some interests on their own. They then jointly create a Federal body and ask that body to look after a small set of common interests on their behalf and of their Citizens.

Clause 1 lists the name of the Common European Interests. This gives a good idea of what these interests mean. For a better idea of their content, see Appendix III A. The Appendix describes the procedure for the vertical separation of powers which gives indications of the subjects of policies that are entrusted to the care of the Federal authority.

Clause 2 explains what a centripetal federation is: the parts create a whole, a centre, which is empowered by the parts to look after common interests that individual States can no longer look after on their own. Although the list of Common European Interests is exhaustive, Clause 2 offers a window for increasing or decreasing it if new circumstances warrant. Naturally, this must be done via the procedure of Appendix III A and of the procedure to amend the Constitution. New circumstances can be: a new insight in the meaning of the values and norms of the constitution; a new insight in the meaning of Common European Interests that affect at least three states and have the potential to escalate to other states; the realization that the scale of new circumstances requires a uniform, efficient federal response.

Clause 3 refers to Appendix III A that regulates the procedure of the vertical separation of powers. See the end of this Explanation on Article III.

More powers than the ones in Section 2

It is to be expected that the practice of the European Federal Union will show that the Houses of the European Congress - just like those of the US Constitution - feel that they do not have enough powers with the exhaustive Common European Interests mentioned in Section 2. A system of 'additional powers' will undoubtedly develop. An expansion of the complex of powers of both Houses that may be at odds with the intentions of the Constitution. One should think here of the following - potential - developments.

One of the most important is called 'Congressional Oversight'. This oversight - organised mainly through parliamentary committees (both standing and special), but also with other instruments - concerns the overall functioning of the Executive branch and Federal Agencies. The aim is to increase effectiveness and efficiency, to keep the executive in line with its immediate task (execution of laws), to detect waste, bureaucracy, fraud and corruption, protection of civil rights and freedoms, and so on. It is a comprehensive monitoring of the entire policy implementation. This, by the way, is not something of the recent past in the US. It arose from the inception of the Constitution and is an undisputed part of the ingenious system of checks and balances. It will undoubtedly develop in the same way in Europe.

The Constitution does not know this 'Congressional Oversight' in so many words, but it is supposed to be an inalienable extension of the legislative power: if you are authorised to make laws, you must also be authorised to control what happens in their implementation. It is self-evident in an administrative cycle. Of course, there have been attempts to demonstrate with a strict interpretation of the US Constitution that this form of 'Implied Powers' is not in accordance with the Constitution. However, the US Supreme Court has always rejected this claim. This is in line with the vision of President Woodrow Wilson, who saw this parliamentary oversight as being just as important as making laws: "Quite as important as legislation is vigilant oversight of administration."[1]

[1] For more information on these issues, see Chapter 10 of the aforementioned Toolkit: https://www.faef.eu/wp-content/uploads/Constitutional-Toolkit.pdf.

Explanation of Section 3

Clause 1 restrains policies and actions that may be crushing for biodiversity or that, for example, polluting energy companies are opened or remain open in violation of climate agreements. This ban must make a positive contribution to energy and food availability and security.

According to Clauses 2 and 3 of this Section, neither the States of the Federation, nor the Federation itself, may introduce or maintain regulations which restrict or interfere with the economic unity of the Federation. Again, powers not expressly assigned to Congress by the Constitution in Article III, Section 2 rest with the Citizens and the States. This is the other side of the coin called 'vertical separation of powers'. Nevertheless, in America it was considered useful and necessary at the time not only to place limits on Congress in their Article I, Section 9, but also to remind the States that their powers are not unlimited. To this end, their Article I, Section 10 - our Article III, Section 3 - stipulates what the States may not do.

Clause 4 imposes the same limitation on the legislative power of the States as that of the Federation in order to maintain legal certainty, not to affect the exercise of judicial power and to safeguard rights of Citizens in force or enforced. It is also important, a subject that has often been addressed by the US Supreme Court, that States may not legislate to override contractual obligations. Legal certainty for contractors and litigants is of a higher order than the power to declare a contract or a court decision ineffective by law.

In Clause 5, the provision that none of the member States of the Federation may create its own currency (taken from James Madison's Federalist Paper No 44) is a clear warning to some EU Member States considering returning to their own former national currencies. Nevertheless, states are allowed to issue bonds and other debt instruments to finance their deficit spending. In other words, we are proposing to create a financial system similar to that of the USA.

Clause 6 states that export and import duties are not within the competence of the States unless they are authorised to do so. They may, however, charge for the expenses they incur in connection with the control of imports and exports. The net proceeds of permitted levies must fall into the coffers of the Federation. This matter is likely to have a high place on the agenda of the previously recommended six delegates of the House of the States (without voting rights) delegated by the ACP countries to the European House of the States.

Clause 7 emphasizes once again that defence is a federal task. On the understanding that the European Congress may decide that a Member State shall accommodate on its territory a part of that federal army and keep it ready to act in case of emergency.

Explanation of Section 4

In this Section 5 we have included a number of additional rules to combat political corruption. Because gigantic sums of money are spent on election campaigns in America, there is a saying: "Money is the oxygen of American politics". In our federal constitution for the United States of Europe, Article III, Section 5 contains Clauses justifying the adage: 'Money should not be the oxygen of European politics'.

Appendix III A - The procedure for the vertical separation of powers

By ratifying the Constitution, the Citizens adopt the limitative and exhaustive list of the Common European Interests. The question, however, is: how can one properly determine which powers are necessarily needed to enable the Federal Authority to do its job? For that, a procedure is needed. A procedure of debate and negotiation within which the Citizens (direct democracy) and the States play a prominent role. For this purpose, Clause 3 refers to Appendix III A which is an integral and therefore mandatory part of the Constitution, but for any future adjustment it is not subject to the amendment rules of the Constitution.

If the Constitution is ratified by enough Citizens to establish the Federation

the limitative and exhaustive list of the Common European Interests will be established. The meaning of this is: the Citizens have spoken; that list is non-negotiable during the debate and negotiation necessary to determine which powers should be entrusted – by means of that vertical separation of powers - to the Federal Authority, to enable the Federation taking care of the Common European Interests.

Let us repeat once again that the Member States retain their sovereignty in the sense that they do not transfer or confer parts of their sovereignty to the federal body and would thus lose those sovereignty. What they are doing is entrusting some of their powers to the federal body because that body can look after Common European Interests better than the Member States themselves. Thus, the Member States make their relevant powers dormant. The effect is shared sovereignty.

The vertical separation of powers will always be a matter of debate and will sometimes require adjustment. That is why the outcome of the debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers will be another Appendix to the Constitution: Appendix III B. The Appendix III A on the procedure of the process of the vertical separation of powers and the future Appendix III B, containing the result of that procedure, are integral parts of the Constitution but might be adjusted during the years without being subjected to the constitutional amendment procedure. This is to prevent that any necessary adjustments of the vertical separation will force to amend the Constitution itself.

On the basis of three principles, the founding fathers of this Constitution lay down the following procedure for determining the vertical separation of powers.

Principle 1 – from bottom to top

It would be a severe system error to arrange the allocation of powers from top to bottom. Wherever possible in the construction of a federal state, one should always work from the bottom up. That is a ‘commandment’ of the centripetal way on which this federal Constitution is based. This requires asking the Member States which parts of their complex of competences they wish to make dormant, so that the federal body can dispose of them to take care of the Common European Interests.

One must be careful not to think in terms of decentralization. Decentralization is ‘moving from top to bottom’: the center shares parts of its powers with lower authorities. This does happen in federal states that are centrifugally built: a centre creates parts. But the effect of such a course of action is that there will always remain unitary/centralist aspects. If countries such as Spain and the United Kingdom were to decide to further decentralize their already existing devolved autonomous regions into parts of a federal state, they would run the risk of creating a relatively imperfect federal state as well.

Principle 2 – debate and negotiation on Common European Interests

If the electorates of some European states ratify the Constitution by a majority, and if their parliaments follow the will of their people, the debate and negotiation on the powers that the Member States entrust to the Federation starts. This process is as follows:

a) Internal deliberation by individual Member States

Each Member State has two months to prepare a document in which it puts forward proposals on the powers it wishes to entrust to the Federal body. In total, they draft one document for each Common European Interest. In doing so, they give an insight into the way in which they think the Federal body should be vested with substantive powers and material resources. A Protocol establishes the requirements that the documents must meet in order to be considered, among which the organization of the way Citizens participate in that process (direct democracy). The central requirement is that they must deal with the representation of Common European Interests that a Member State cannot (or can no longer) represent in an optimal manner itself.

b) Aggregation of the documents

Under the leadership of FAEF, a Transition Committee is created beforehand to regulate the transition from the treaty-based to the federal system. This is where the Citizens come in as well: direct democracy. Led by FAEF, that Committee consists of (a) non-political Experts on the Common European Interests and (b) non-political Citizens. Point (a) is required for expertise. Point (b) is required to prevent the deliberation and decision-making on the vertical separation of powers from degenerating – as has been the case in the treaty-based intergovernmental EU-system since 1951 – into nation-state advocacy. The Transition Committee aggregates the documents of the Member States into a total sum of powers to be vertically separated, and the substantive and material consequences. Two months are available for this.

c) Final decision-making

The aggregated document is the agenda for a one week deliberation on each Common European Interest. Under the leadership of the Transition Committee, final decisions are taken on the best balanced allocation of powers from the Member States to the Federal body. This final document will be an integral Appendix III B of the constitution. After its implementation in the federal system practice will show when, why and how Appendix III A on the procedure of the vertical separation of powers needs improvements, so that the Appendix III B on the result of that procedure must undergo improvements as well.

d) The start of the construction of the federal Europe

The result of c) marks the beginning of the building of the federal Europe. Guided by a Transition Committee of Citizens, the Member States determine concretely how the federal body with a limited number of entrusted powers of the states should represent a limited amount of Common European Interests. It marks a barrier between the tasks of the federation and the fields in which the Member States remain fully autonomous and the federation cannot become a superstate.

Principle 3 - Debatable and negotiable subjects

Taking from the limitative and exhaustive list of Common European Interests of Section 2, Principle 3 contains non-exhaustive examples of topics on which the debate and negotiations may take place.

The formula is as follows:

The European Congress is responsible for taking care of all necessary regulations with respect to the territory or other possessions belonging to the European Federal Union, related to the following Common European Interests:

1. The livability of the European Federal Union,

by regulating policies against existential threats to the safety of the European Federal Union, its States and Territories and its Citizens, be they natural, technological, economic or of another nature, or concerning the social peace.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on all natural resources and all lifeforms, on climate control, on the implementation of climate agreements, on protecting the natural environment, on ensuring the quality of the water, soil, air, and on protecting the outer space;

(b) to regulate policies on preventing and fighting pandemics

(c) to regulate the policy on the safety and availability of food and drinking water;

(d) to regulate the policy on preventing scarcity of natural resources and dysfunctional supply chains;

(e) to regulate the policy on social security, consumer protection and child care;

(f) to regulate the policy on employment and pensions;

(g) to regulate the policy on health throughout the European Federal Union, including prevention, furthering and protection of public health, professional illnesses, and labor accidents;

(h) to regulate the policy on justice and on establishing federal courts, subordinated to the European Court of Justice.

2. The financial stability of the European Federal Union,

by regulating policies to secure and safe the financial system of the Federation.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on federal tax, imposts, and excises, uniformly in all territories of the European Federal Union, on the debts of the Federation, on the expenses to fulfill the duties imposed by this and on borrowing money on the credit of the Federation;

(b) to regulate the policy on installing a fiscal union;

(c) to regulate the policy on supervising the system of financial entities;

(d) to regulate the policy on coining the federal currency, its value, the standard of weights and measures, the punishment of counterfeiting the securities and the currency of the Federation.

3. The internal and external security of the European Federal Union,

by regulating policies on defence, intelligence and policing of the Federation.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on raising support on security capabilities, among which the policy on one common defence force (army, navy, air force, space force) of the Federation, on compulsory military service or community service, and on a national guard;

(b) to regulate policies in the context of external conflicts, policies on sending armed forces outside the territory of the Federation, on military bases of a foreign country on the territory of the federation, on the production of defensive weapons, on the production of weapons for mass destruction, on the import, circulation, advertising, sale, and possession of weapons, on the possibility of bearing arms by civilians;

(c) to regulate the policy on declaring war, on captures on land, water, air, or outer space, on suppressing insurrections and terrorism, on repelling invaders, and on fighting autonomous weapons;

(d) to regulate the policy on fighting cybercrimes and crimes in outer space;

(e) to regulate the policy on one federal police force;

(f) to regulate the policy on one federal intelligence service;

(g) to regulate fighting and punishing piracy, crimes against international law and human rights;

4. The economy of the European Federal Union,

by regulating policies on the welfare and prosperity of the Federation.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on the internal market;

(b) to regulate the policy on transnational production sectors like industry, agriculture, livestock, forestry, horticulture, fisheries, IT, pure scientific research, inventions, industrial product standards;

(c) to regulate the policy on transnational transport: road, water (inland and sea), rail, air, and outer space; including the transnational infrastructure, postal facilities, telecommunications as well as electronic traffic between public administrations and between public administrations and Citizens, including all necessary rules to fight fraud, forgery, theft, damage and destruction of postal and electronic information and their information carriers;

(d) to regulate the policy on the commerce among the Member States of the Federation and with foreign nations;

(e) to regulate the policy on banking and bankruptcy throughout the Federation;

(f) to regulate the policy on the production and distribution of energy supply;

(g) to regulate the policy on consumer protection;

5. The science and education of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on the improving the level of wisdom and knowledge within the Federation.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on scientific centers of excellence;

(b) to regulate the policy on transnational alignment of pioneering research and related education;

(c) to regulate the policy on the exclusive rights for authors, inventors, and designers of their creations;

(d) to regulate the policy on progress of scientific findings and economic innovations.

6. The social and cultural ties of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on preserving established social and cultural foundations of Europe.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on strengthening unity in diversity: “Acquiring the new while cherishing the old”;

(b) to regulate the policy on arts and sports with a federal basis.

7. The immigration in, including refugees, and the emigration out of the European Federal Union, by regulating immigration policies on access, safety, housing, work and social security, and emigration policies on leaving the Federation.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate policies on access – or denial of access - to the Federation, on security measures against terrorism and cybercrime related immigration, on mode of housing, employment, social security;

(b) to regulate policies on leaving the Federation.

8. The foreign affairs of the European Federal Union, by regulating policies on strengthening the Common European Interests in the interest of global peace, social equality, economic prosperity, and public health.

Potential topics for debate and negotiation on the vertical separation of powers:

(a) to regulate the policy on external cooperation to strengthen the policies on the foregoing Common European Interests.

(b) to define the means by which this common interest is promoted, e.g. through cooperation by States, especially concerning international trade (what is trade, with whom, under what conditions), developmental projects (what projects, with what partners, under what conditions), disaster relieve, projects to mitigate (the consequences of) climate change/global warming.

(c) to regulate policies to promote global federation.

To sum it up, correct thinking about federalizing is as follows

1. The Common Interests are the same as a Kompetenz Catalogue. It is a limitative and exhaustive list of concrete interests of a common European nature. They must be formulated in an abstract, generic way. In other words: the common interests must have a name. For example, 'The financial stability of the European Federal Union’.

2. Although the list of Common European Interests is exhaustive, the Constitution must provide for the possibility of adapting that list. The constitutional amendment procedure and that of Appendix III A shall apply.

3. These common interests must be promoted by means of policies. To design and implement policies, the federal body needs powers. This requires a so-called vertical separation of powers: the states entrust a limitative and exhaustive list of powers to the federale entity.

4. Because we are building a classic centripetal federation (i.e., from the bottom up), it is up to the Member States to decide which powers they want to entrust to the federal body. This is the key to limiting a possible Pandora's box of an endless list of policies for free application by the federal body.

5. This methodology is a natural limitation to the bottom-up determination of what member states want to entrust to the federal body. They might want to limit themselves and in that (defensive) attitude lies the perfect opportunity to clarify together what the real European interests are. The purpose of making a federation is not to enable a federal body to act as a new ruler but to look after essential European interests.